A very simple illustration of the mind/body problem

The previous entry #015, ended with a note announcing a rudimentary picture of the interplay between science of matter and science of mind, the top two quadrants of Fig. 47. Constructing such a picture is a challenge, akin to asking a fish to draw a picture of water. Any moment of our waking life is shot through with material and mental elements. Where to start?

Any experience we have seems connected to our material body, while it is experienced in our mind. Whether it is a sensory experience, like seeing a stone, or a thought, or a feeling, like that of joy, and often a hybrid, like enjoying the reflection of sunlight on a multicolored stone while thinking about which type of stone it could be. In short, life as we know it is made up of embodied experience in one way or another.

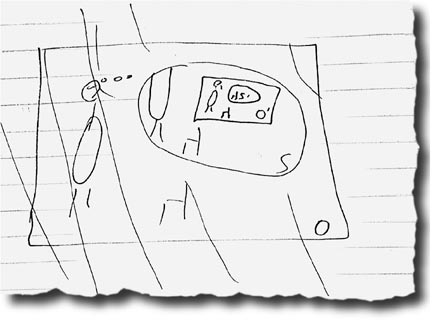

Fortunately, my training as a physicist has taught me to not hesitate simplifying anything down to a few strokes of a pen as a starting point, before filling in more detail where and when necessary. Any two concepts can be connected by labeling them A and B, and then drawing a line or an arrow between them, showing "what relates to what", or by drawing circles around them, showing "what includes what" in some way, to mention only some possibilities. Fig. 48 below provides such a picture, taken from the front page of the Science Section of the New York Times on April 29, 1997.

A week earlier I was interviewed by Jim Gorman, who had called me to see whether I would be interested in talking about my ideas concerning physics and consciousness. The trigger was that my friend and colleague Roger Shepard and I had given a presentation in the second Tucson conference in a series called "Toward a Science of Consciousness", less than a year before, which resulted in an article titled "Turning 'The Hard Problem' Upside Down & Sideways" in the Journal of Consciousness Studies, 3, No. 4, 1996, pp. 313-329. The "Hard Problem" here refers to "The Hard Problem of Consciousness", mentioned in the caption of Fig. 42 in entry #014, a concept introduced by David Chalmers during the first Tucson conference in 1994.

While the NYT article made the news only on 4/29, 1997, it is gratifying to see that our 1996 paper is still being discussed as having made a major contribution to the new wave of consciousness studies in the nineties. In "The Blind Spot, Why Science Cannot Ignore Human Experience", a book published earlier this year by Adam Frank, Marcelo Gleiser & Evan Thompson, they start the section "A Science of Consciousness in Which Experience Really Matters" [pp.218-220] with:

Three decades ago, when David Chalmers first coined the term “the hard problem of consciousness” and called attention to its importance, a few scientists made the bold suggestion that the intractability of that problem within what we are calling the Blind Spot means that we need to reframe science in order to investigate consciousness. In two independent papers, published in the same issue of Journal of Consciousness Studies in 1996, astrophysicist Piet Hut and cognitive psychologist Roger Shepard, and neuroscientist Francisco Varela, made the case for a major overhaul of the science of consciousness based on recognizing the primacy of experience.

This was the context and the first topic Jim asked me about during our very amicable conversation over breakfast, around the corner from where I lived.

I had brought a notepad, since as a physicist I always prefer sketching out ideas on a blackboard, and a piece of paper is the next best thing. I'm glad I did. In my publication record of a couple hundred scientific articles, the picture that I drew that morning is still unique for me in that it got produced, submitted, accepted, and published, all within one week.

But seriously, this spontaneously drawn picture helped me too, to see more clearly what I had earlier been trying to express in words to Jim. It contains the central elements of how most of us in a Western culture view the world, and our place in the world, for our body as well as our mind.

Starting with matter O

To start with, we tend to consider ourselves as having a body and a mind, both of which are located in a very small corner within a huge Universe. That overarching Home of ours is well over a hundred trillion trillion times the size of our body. As for locating our mind, whether in our brain or in our body as a whole, or perhaps in an area around our body, most people would probably not imagine our mind being much larger than, say, one tenth of a trillionth of a trillionths of the size of the Universe that makes up our personal little corner of the world.

The outer rectangle in Fig. 48, labeled O, stands for the observable Universe (just imagine that it would be stretched by the large number mentioned above). The term "observable Universe" is what we astrophysicists use to indicate that part of the Universe that has become visible to us since the Big Bang. Anything further away is literally still terra incognita, an area from which neither light nor any other carrier of information has been able to reach us yet, given the finite speed of light.

Within our observable Universe, we consider the body of an individual person to be part of objective reality, hence the label O: the body as a material entity, objectively present in the material world. Here "objective" means: anyone one with a normally functioning body and mind would agree that the person depicted is standing there in front of an equally objectively present chair.

So far so good, but how can we depict the mind of that person? Would it even be correct to say that it has a physical location? Strictly speaking, perhaps not. Philosophers might want to call that a category mistake. But most physicists and biologists, viewing our minds as some kind of emergent property of the very complex systems that our bodies are, would almost by definition point to our bodies as, at least roughly, the location of our minds -- and so would most people, at least in our Western culture.

But to make room for a mind in our picture in a very simple way, I borrowed the device of a thought bubble, as used in cartoons, comics, and animations. The bubble depicted in the figure is labeled S, which stands for the subjective nature of one person's mind, which is not accessible to others. In addition, we cannot see our own head without using a mirror or taking a picture, which led me to draw only part of the person's body as visible in the S bubble.

Starting with mind S

Even though we started with the material world as the container of our bodies, and of any other physical object for that matter, we cannot as individuals be certain of the objective existence of matter. If I see a chair, I see an image of a chair, which makes me conclude that there must be an object looking like a chair, which is most likely objectively present in that location. Just by closing our eyes for a second, it is completely clear that the visual impression that we are aware of in our mind is not the material chair, but a mental awareness of visual aspects that I consider as an indication of the presence of a chair.

The same is true for sound, smell, taste or touch. We can lose or diminish the vividness of their presence. We can even replace them by going into a virtual reality in which we feel/sense that we are in a different reality altogether. Whatever we can ever experience are . . . experiences, stirrings in our mind. We simply cannot put a rock in our mind, though we can investigate a rock in great detail, and construct in our mind a very reliable understanding of many aspects of that rock as it is experienced.

The crucial point here is that we do not have empirical access to any form of matter, where empirical is defined as given in experience (see entry #003 for a more detailed discussion). Of course, for all practical purposes, it makes sense to identify the physical presence of an object with the sense impressions we receive from that object. But strictly speaking, if we define our mind as the realm in which we experience anything, be it sense impressions or thoughts, feelings, memories, etc., then in terms of direct experiences, we can *never* leave the thought bubble S depicted in Fig. 48.

Where, then, are material objects located, from an empirical point of view, in our figure? Not in O, since each object in O that we want to empirically investigate only shows up as an experience in our mind, in S. This simple conclusion is illustrated in Figs. 48 and 49 in two ways.

First, even though the body and mind shown in the figure are located within the much larger realm of O, the one and *only* part of the figure to which we have direct access is the S bubble. As in the case of virtual reality, our feelings and any other experiences we may have are real feelings and real experiences. In contrast, the physical world that we think we directly experience as O, outside our mind S, does not have this kind of reality status. It is not empirically real. Instead, it is a constructed world, informed by our experiences, and constructed in our mind.

Since it is constructed by us, in that respect it is not different from the way the world in a novel is constructed. To indicate this lack of empirical accessibility, I symbolically used a few slanted lines to cross out O, as a realm we cannot obtain empirical cognition about. We can talk about it, we can decide to agree about its existence, and we can use our knowledge encoded in the theoretical structure O, but we cannot have direct access to it. It has the nature and function of a map. This of course raises the question of where that map is located. This is our second question.

Given that we do experience what we call physical objects, if those experiences are not located in O, they need to be located somewhere in S, symbolic for our whole mind. Where? Let's make an inventory of S, our mind. What do we find there? Fantasies, memories, expectations, thoughts, feelings of all kinds, moods, you name it; and of course in addition to all those "inner" experiences, in S we also find all of our "outer" experiences. While we consider the latter to be direct experiences of the outer world, nonetheless, they are still experiences so they have to take up some special quarters inside S. That "outer" realm of experiences is indicated by the rectangle O', lying fully within S, and corresponding closely, we think and we hope, to the postulated but totally inaccessible realm O.

Ending with mind S'

The only conclusion we can draw is that the chair we think we see is the chair inside O', and so is our body insofar as we consider it to be "in the world out there", inside O'. Of course, when we are hungry or cold or when we feel happy or relaxed, those feelings can directly occur outside O', as "inner" feelings, but still inside S. But as soon as we ask what the location is of our empty stomach, which we think causes our hunger, we switch to the "outer" realm O', located deep within S.

It may take quite a while to track all these arguments, allowing ourselves to become familiar with some of the unexpected implications. But when we follow the logical consequences of the definition of a mind as the space or realm in which experiences take place, we have no choice but to switch some of the polarities in our inner/outer dualities. What we normally consider to be an "outer" world in which we move around, is effectively "inner", as O' contained within our mind S as a whole. And what we normally consider to be "inner" feelings, memories, etc., don't have a place inside O', so we have to conclude that all those inner experiences must lie in the "outer" parts of S, outside O'.

But we are not finished yet. One final exploration has been left out so far. If we deal most directly with our bodies only within O', what happens when we consciously try to deal with our mind? Well . . . there *seems* to be only one logical conclusion: we will have to draw a thought bubble S' accompanying our body inside O'. [Note: as we have seen already above, there *is* a more logical conclusion, namely that S is the real mind, which is typically overlooked]. When we talk about "my mind" or "my consciousness" we talk about a mental companion of our empirically accessible body in O'. And the only place we can find in O' is . . . S', the objectified version of what S is within O -- objectified in that we have to give it the same status as other objects within O'.

In other words, we have empirical access to the chair that we tend to locate in O through our copy of the chair in O', which is part of a set of experiences in our mind S. Similarly, we have access to our own body located in O through the copy of our own body which we deal with in O'. And since we consider our mind S to be something that accompanies our body in O, we have to be consistent in dealing with our mind through the contents of our mind that we have to locate in S', the objectified mind that seems to accompany our experience of our body in O'.

But now we are reaching a very strange conclusion. We have to admit that there are *two* very different ways of talking about "our" mind. There is the "outer" mind S, the sum total of all of our experiences. And then there is the "inner" mind S', the one we point to if we talk about our mind, some of us pointing to our head, some to our heart, depending mostly on our culture.

What we actually are using, as our mind that contains all of our experiences, is S. In contrast, S' is a projection of what we think is going on in our mind S. In that sense, S' is our map of S, just as O' is a map. The big difference is that O' is a purely constructed map, made up without any access to the imaginary O, whereas S' is a map that is produced based on our actual access to S.

Why don't we point in all directions away from ourselves, as "outer" as we can indicate, when asked to locate our mind? The answer is that while we are the users of our mind S, that use is so tacit and so fully transparent, that we are left no choice but to point to S', the objectified and thus reified image of S, that has been made into an object S' within the realm O' of all other experienced material objects.

Jim Gorman quoted me at the end of his figure caption as "Dr. Hut argues that when S and S' are conflated, confusion reigns." I am still grateful to Jim for his keen questioning, which forced me to show my cards and come up with a "creation myth" of an objective world O, a kind of inaccessible paradise. This in contrast to a "mundane reality" O', lurking in a personal copy of a posited reality, a tapestry densely woven from empirical "outer" data, and "inner" data that are at least partly personally and culturally determined. The latter are always tacitly present but for a large part never acknowledged.

Connections with our initial experiments

In entries #003 through #005, we first explored the realm of experiences S, which the German philosopher Husserl opened up in a systematic way through his choice of epoché. We then went beyond S, so see what remains when we drop the duality of subject/object polarization, following hints provided by the Japanese philosopher Nishida. In doing so, we caught our first glimpse of a nondual reality, as a realm of sheer appearance. Like O, it was postulated to enclose the realm of pure experience S, and like O, it went beyond subjectivity, but unlike O, it *also* went beyond objectivity. To make any sense of this will require a detailed analysis, which will take much of the current Part 3.

At the end of entry #005, I decided to dedicate the following several entries to a semi-popular introduction of the way theories in physics have evolved during the four centuries of modern science. This would grow out to seven entries in total, more than I initially expected, in that way naturally forming Part 2. In each of those entries, I dedicated special sections to making explicit parallels between theory formation in the history of modern physics and possible theory formation in a new science of mind. My sole aim was to lay the foundations of theory formation for science as a whole, starting with many worked-out examples of natural science, as an inspiration for our still-to-be-worked-out examples of a science of mind.

While writing entries #006 through #012, several friends and colleagues asked me why I did not write more about the so interesting and more juicy experiments that I had just started to sketch. My answer was always: we didn't have yet enough of a sound basis on which to erect theoretical towers. By now we have established enough of a foundation to move forward with the experiments introduced around the ideas of Husserl and Nishida.

In the rest of the current Part 3 we will explore in far more detail what we could only begin to see in entries #003 through #005, namely two ways of "going beyond". First to go beyond matter, by seeing how all forms of matter are given in the mind. Second, to go beyond "my mind" as opposed to "external objects", to begin to explore a nondual realm of sheer appearance, in which both subjects and objects are forms of appearance, and as such deeply and fundamentally related.