The FEST program

As summarized already in entry #000, in this FEST Log, of which you are now reading entry #015, my proposal is to start a new form of science, not directly modeled on the way natural science studies matter, but rather starting from the same core methodology. As I wrote in the previous entry #014, the three elements that I consider essential in science do not include many aspects that people think about immediately when hearing the word "science".

For a science of mind, key experiments do not involve any machines, or any other material tools. In the realm of mind studies, mind tools are called for. This stands in direct analogy to the study of the stars, which use telescopes as appropriate tools, and to the study of biological cells, for which tools are microscopes.

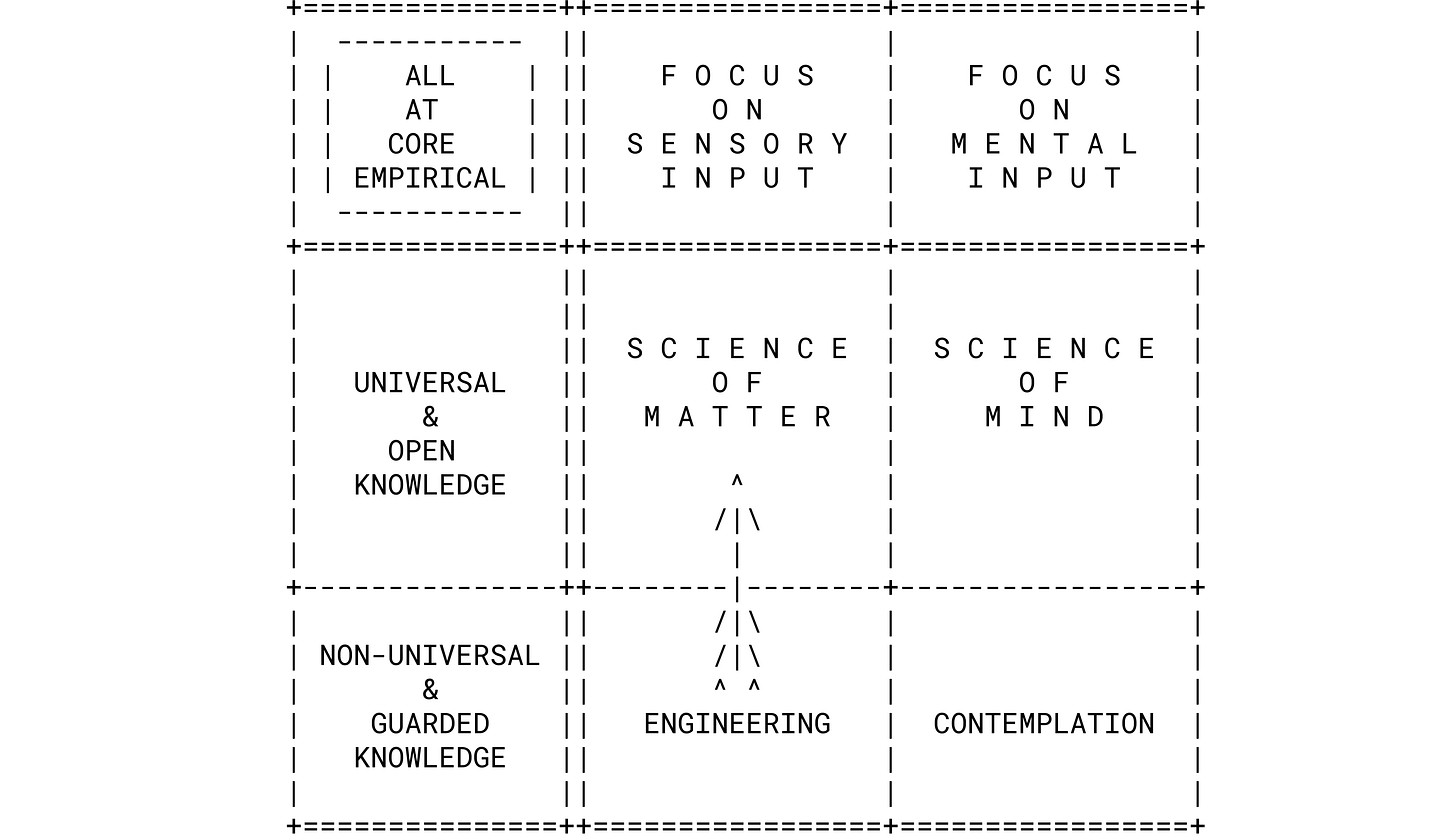

For a science of mind, theory may or may not involve forms of mathematics, that question is still to be decided, depending on what natural form theories will take in this new field, over time. However, three things are clear: working hypotheses will remain working hypotheses; a self-governing community of peers will remain a self-governing community of peers; and experiments will remain the ultimate judge over any theory, to deserve the label "science", in my opinion. This is implied in the label "science of mind" for the upper right quadrant in Fig. 43.

Science and contemplation

The foundational phase, Parts 1 and 2 in the FEST Log, was focused on a comparison between the established science of matter and a possible science of mind. The former got started by Galileo and his contemporaries. The latter, to the best of my knowledge, has not yet been attempted in its full generality. The comparison between the two implies comparing the top two quadrants depicted here in Fig. 43.

The main theme in the FEST Log, Part 3, of which this is the second entry, will be a different comparison. Instead of taking two forms of science, one yet to be firmly established, I will now focus on two recognized human activities, both with roots reaching back through millennia of history, namely science and contemplation, as shown in Fig. 44.

Contemplation so far has not yet produced a shared global community, the way science has. Nor are its deepest insights shared in the open way as done in science, quite likely initially for good reasons, since unrestricted knowledge can be a dangerous thing. The science community, too, has developed structures that aim at preventing misuse. For example, publication of recipes for developing biological weapons of various kinds is excluded from the otherwise "open source" attitude of science. But the basic approach remains to share scientific results, with only some exceptions.

Historically there have been many esoteric forms of contemplation that have started from a basic approach of secrecy, not that different from engineering guilds with their trade secrets. But in these musings I am aware that I am stepping outside my area of expertise, and this kind of discussion is something I hope to see developing soon in a future community of peers for a science of mind.

No science of matter without a prehistory of engineering

As discussed at some length already in entry #002, and further in entry #006, there would be no science of matter, had there not been a flourishing history of activities, spanning millennia, before Galileo started to formulate the scientific method in its first outline. Now that we have given a name to all four squares in our 2x2 matrix, we can draw a few arrows between them, to illustrate their connections in Fig. 45.

No science of mind without a science of matter

From the start, I have found my main guidelines in the great success story of natural science, the science of matter. The main challenge has been to see how we can extract the core ingredients of its success as a guide toward starting a science of mind, without smuggling in elements that are only relevant for the study of matter.

I have been working on this challenge, on and off, ever since I came across some simple meditation instructions when I was 17. Almost immediately I was struck by the similarities with previous activities I had engaged in from age 12 onward, such as building my own telescope, performing chemical experiments, and modding older motorcycles, to name a few. I noticed that, hey, meditation seemed no different from all those other activities, the only difference was the nature of the laboratory I was using, together with some friends.

Instead of the blacksmith shop of the father of a friend, where we tuned our motorcycles, or the shed in which we worked with chemicals, my lab now was . . . my own mind. Other than that, the instructions were remarkably similar. Make sure you clean the space you are working in, having your tools at hand. Practice to make sure that you know how to use those tools. The only difference was that both workspace and tools were no longer material, but mental.

To my surprise, when I tried to share my discovery, nobody seemed to grok what it was that I was trying to express, while groping for words -- at that time I had zero vocabulary to express what it was, that I saw so clearly in my intuition. Fast forward 54 years: although my vocabulary improved, by and large reactions are still similar, although more and more people I talk with are now beginning to show some degree of cautious interest.

Let's return to the beginning of this section. How can we hope to extract the core ingredients of the success of science, to use as a guide toward starting a science of mind, without smuggling in elements that are only relevant for the study of matter? After summarizing those ingredients in entry #001, we got a quick preview, more like a teaser, in entries #003 to #005 from the side of experiments, to get our feet wet, followed by a switch to theory building in entry #006.

Finally, in order to start laying it all out, entries #008 through #012 showed a picture book of theory formation in physics, the simplest and most fundamental branch of science of matter. Fig. 46 indicates my approach of trying to be as conservative as we possibly can, in trying to see what we can salvage from a science of matter, before plunging into the uncharted territory of a science of mind.

No science of mind without a prehistory of contemplation

Finally, to complete the connectivity of the four quadrants in our 2x2 matrix, we can add the last hinge, between contemplation and science of mind. Fig. 47 shows how a science of mind naturally should start with the resources offered by a hundred generations of written texts, from around 500 BC onward, in Europe as well as Asia. This enormous treasure trove bears witness to the development of mind engineering, no less innovative and fascinating as the history of matter engineering.

Let me make clear that I am not directly comparing contemplation with engineering. Each has their own goals and methods. But in both cases there have been prescientific attempts, perhaps more properly called protoscientific, which have come close to fulfilling all three essential elements of the methodology of science. In engineering, Archimedes is an example of someone who came close to inventing and applying forms of calculus, before Newton and Leibniz did so.

Even more so in contemplation, working with what is sometimes called "view and practice" is very parallel to "theory and experiment", and indeed both go hand in hand with contemplative training as well. And the use of working hypotheses, dropping any trace of belief or disbelief is a standard practice in contemplation. To give just one reference, from medieval Christian mystics: The 14th century book "The Cloud of Unknowing", written by an anonymous author is a perfect example. The central idea of a working hypothesis, of dropping both belief and disbelief, to reach a state of unbelief combined with undisbelief, in short, of Un-knowing, is already present in the title, well before the start of modern science!

The one element that neither engineering before 1600, nor contemplation so far, has included is the presence of a world-wide self-governing community, whose members strive to find agreement among each other. In many if not most cultures, inquisitive young contemplatives who dared to challenge the existing status quo were met with a cold if not aggressive attitude, sometimes life threateningly so. I don't think there have been many self-governing long-lasting contemplative communities that avoided the development of a priest class that was trying to limit their freedom.

In addition to the problem of restrictions on self-government within contemplative circles, the general lack of collaboration between different brands of contemplation was another problem, placing them in a prescientific stage of development. Simply put, when scientists realize that there are different ways to approach the same problem, there is a centripetal tendency to sort things out. It is my impression that by and large among contemplatives the main tendency is centrifugal.

As I mentioned before, in making such statements I am stepping outside my area of expertise, and I very much look forward to discussing these problems in a future community of peers for a science of mind. For now, let me stick my neck out: when different contemplative cultures met each other, the general reaction was either avoidance or debates in which each side tried to prove that their opinions were "right", or at least closer to reality than that of the other. In contrast, it would be very odd to see different kinds of physics being developed in different places, without serious attempts to find ways to transform each one into the other.

Instead, as I mentioned in entry #012 in the section titled "Mapping the structure of atoms", when quantum mechanics was discovered almost simultaneously in very different forms, immediately the search was on. The leading physicists set out to analyze the differences, with the result that in just one year they developed an understanding of how the two approaches could be transformed into each other without contradictions.

What next?

In our next entry #016, we will start to sketch a most rudimentary picture of the interplay between science of matter and science of mind. And we will do so in a single map of the nature of reality -- so simple that only children, scientists, and contemplatives would dare to go there.