Extending the analysis of the New York Times figure

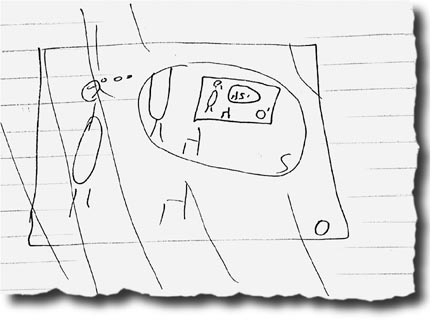

In the previous entry, #016, we saw how we do not have direct empirical access to the objective world (represented as O in Fig. 49). In fact, we use part of our subjective mind, S, to maintain a constructed three-dimensional picture, O', of our concept of O. This concept of the objective world coexists within our subjective mind alongside other parts outside O', where more subjective, perspectival impressions of the outer world reside, together with subjective feelings, thoughts, memories, etc. This simple sketch illustrates the mind/body problem. To be more precise: O' contains our subjective reconstruction of what we consider to be the objective structure of the world in O, outside S. These considerations take a while to get used to, so let us recapitulate in more detail what we saw in the last entry.

The mind, S, is shorthand for all that we experience, at any given time. Most if not all of the time, when we see and touch a chair, we think and talk about the chair as being "out there", outside "me", outside the "body and mind" that together make up me. In the very simple sketch in Fig. 49, the body part of "me" would then be the outer stick figure in the box O that represents the world, and the mind part of "me" would be the thought bubble S, all very schematic of course.

Now where is the chair that we see? Not the chair in O. When we close our eyes briefly, the chair we see disappears. In fact, everything around us disappears, as far as we can see. When we open our eyes again, once more we see our legs and also the chair, right in front of our legs. Note that we can't see our own eyes, or our ears for that matter, no matter in which direction we look, unless we use a mirror, or a reflection on a body of water.

The chair that we see is also not in O', since O' is our interpretation of the world, what appears for us when we see and know the world, based on the input of our eyes, and more generally of all of our sense organs. In everyday life, the "look and feel" of the O' that we experience is exactly what we consider to be O, outside us in the world around us, outside our body and outside our mind. When we close our eyes, we are certain that the chair continues to exist in O, and therefore also in the O' that we habitually take for the outside world. Of the three chairs in Fig. 49, only the middle chair (the one which is in S but outside O') becomes invisible when we close our eyes.

Of course, we know that neither the chair nor our legs disappear when we close our eyes. When asked to describe the "real world" around us, we intend to give a description of the inventory of O. Yet both this description, and how we interpret it, happen within the confines of our mind, not somewhere outside our mind, so it cannot happen in O. Any description we can possibly give must be based on the inventory of O'.

While I may have a strong sense that the chair I am talking about is really outside "me", the "me" that I picture in my mind (the one that I quite literally “have in mind”) is not the "me" in O, outside my mind. It cannot be, because it is my mind that is doing the picturing, the painting. What is more, it is not the me that is drawn here in the outer part of S either. After all, I am not a headless person. Rather I identify with the objective-looking fully present person in O', present in the map I am constructing, moment by moment of what I habitually call the "outer" world, even thought it appears in my mind.

The roles of the three stick figures in O, S, O'

In summary, among the three stick figures in Fig. 49, the one I theoretically identify with is the outer figure in O, though I have no direct empirical access to it. In practice, however, I identify with the innermost figure in O', the one available in my mind. In contrast, the only stick figure that disappears when I close my eyes is the one inside S, but in the S part that lies outside O'.

Once we realize this, we can tell the following story: "What we see is the result of our brain processing the information given to us through our senses. The version of our body we perceive directly is the one inside S, but in the S part that lies outside O'. Meanwhile, we locate the presence of our body as the innermost body in our mental picture of the world O', as a stand-in for O, the outermost background part in Fig. 49. Under normal circumstances, the product of all that processing gives us a good enough understanding of the world we live in, including our own bodily presence in that world."

That may be true for all practical purposes in everyday life, at least for what we have learned to focus on. But the remaining question is: what else is true? This parallels what science of matter has shown us: natural science can give us detailed explanations for the behavior of that part of the physical world that we can see. Yet, to really understand how the physical world operates, it turned out that we had to learn what is going on in parts of that world that are not immediately accessible to everyday observations. We will return to that question later.

Moving in and out of O' while staying in S

Notice the consistency here. The chair inside O' is regarded as the "real" chair, existing in the tangible three-dimensional world. However, if I shift my attention to what I actually see at any given moment, I can notice that I only see the front side of the chair.

I am also, in some way, directly aware of the presence of the backside of the chair, but as a construction that is taking place in the O' part of my mind (within the limits of our very simple sketch). It will even take some effort to realize that my felt presence of the backside of the chair is something that my mind, S, "fills in" even thought it is not actually visible.

The scene outside O' with the actual seen objects is relatively static. Unless we walk around and change our view point, these objects stay visually in place. To make the scene more dynamic, we could introduce a cat or a bird, especially so if both are added together.

In contrast, the part of our mind called O' is hyper dynamic. At one moment we can use our mind to think about the room we are in, aided by our sensory impressions. The very next moment we may picture ourselves walking in a distant city which we have never visited, aided by our memory of having seen photos of that city, or heard accounts from someone having visited that place, while using our imagination to fill in the gaps. In our mind we travel faster than we can jump around in a Google map, and we can travel further too, well beyond the confines of planet Earth.

For example, if we are familiar with M31, the Andromeda galaxy, which is the sister galaxy of our own Milky Way galaxy, then M31 has a place in O' too. In fact there is a place for M31 in the space of S outside O' as well: it shows up as a faint smudge of light in the Andromeda constellation, even for the unaided eye, when we travel to an area where the night sky is still dark enough. Historically, before we knew it was a galaxy, it was known as the Andromeda nebula. The smudge corresponding to the nebula disappears when we close our eyes, indicating that we are outside O' while using our mind S to make direct observations of the "real" world. Yet we interpret the outcome of this experiment as proof that our mental map O' corresponds to what we consider to be objective reality.

Notice the big difference in "size" between O and O', in terms of what it contains. O as the objective reality contains all that humanity currently has knowledge about, and far more: in principle the "real" world includes the whole observable Universe, whatever information of the Universe has potentially been able to reach us within the limits of the speed of light, since the Big Bang. In contrast, the total amount of knowledge that humanity has gathered is a very tiny fraction of that. And for any individual human being, their corresponding O' again contains far less than all that humanity has learned about.

A short list of natural extensions

Given how simple the figure was that we started with, it is somewhat surprising that we have been able to discuss so many aspects of Fig. 49, without adding additional features, so far. One thing we will need to add, before too long, is the presence of more than one person. As in astrophysics, a single star can shine, but it takes two or more stars to interact, and the same is true for people. We have a list of things to do, and one of those tasks is to make a picture for the human two-body problem, how two people use their minds to communicate. We will come to that a bit later on.

Another item on our to-do list is to add existing scientific insights to Fig. 49. Before we make an attempt to add ideas about a science of mind, in the form of the working hypotheses that we presented in entry #003, it would make sense to make room for results from the science of matter, of the type we have presented in Part 2. Fig. 50 presents a very simple initial sketch in that direction.

Seeing the World behind a Science of Matter Filter

In Fig. 50, below, two additional areas have been added to the mind section, S, of Fig. 49. Much of what we find in our mind can be roughly classified as thoughts and feelings, together with memories, fantasies, dreams, and other contents of the mind. We tend to call all those "inner" experiences, in contrast to "outer experiences", related to the sensory input from what we call our environment.

In Fig. 49 we labeled our experience of our physical environment O', in contrast to the area just outside the O' box, still "outer" but not part of what we experience as "objective reality". The area outside the box we tend to label as "subjective reality", as seen from our perspective. What is added in Fig. 50 even further to the outside, towards the edge of S, is a wider area that depicts "subjective inner experiences."

In Fig. 50, the experienced "objective" world, O', is divided into two parts: the outer part in the figure that contains any and all experiences that we associate with our physical existence in the world, and an inner part that describes what we have learned about the material world on the basis of natural science, our science of matter.

The way scientists have obtained knowledge of the physical world is by making measurements in their laboratories under carefully controlled conditions that filtered out unwanted effects. Only some effects can pass through the filters, depending on the type of laboratory. And since the whole of O' is part of our mind S, we can also describe the science filter as a filter of experiences.

Different fields of study allow for different experiences. For example, specific experiences are relevant in physics, while others are relevant in biology, and some may be meaningful in both. For example, cells are recognized in biology as fundamental units, while in physics cells are seen as collections of atoms and molecules, as such not intrinsically different from other aggregates. To indicate what a physics filter can let pass, I have added in Fig. 50 a rather outdated symbolic picture of an atom, presented by electrons whizzing around a nucleus, a far cry from an accurate model, but a recognizable picture that is still often used.

The World of Appearance before a Polarizing Filter

Finally, I will end here with a sneak preview of a different filter, one that I propose to use in a science of mind, depicted in Fig. 51. Unlike the case of the previous figure, I see no way to give even a rough description in just a couple paragraphs. Still, I don't feel like postponing an introduction to what I consider to be at the core of any advanced version of a science of mind.

So let me only hint here at what will become more clear in later entries in the current Part 3 of the FEST Log. My proposal in working with the working hypotheses introduced in entry #003, that experiences are built up out of more primitive elements in the form of appearances, is to replace the outer objective reality O in Fig. 49 with an outer field of appearance A in Fig. 51. The word "field" is not a particularly good term, but I will use it as a placeholder for now, until we can introduce more appropriate terms.