Where is our mind?

In order to watch your mind in operation, all you have to do is to open your eyes and watch how your mind displays for you a first-person view of the world around you. That is one way. Another way is to close your eyes and watch whatever your mind makes up in idling mode in terms of visuals, probably rather nondescript, but at least something. Or you can wait till you fall asleep and watch how your mind displays a dream. And if you can easily visualize images, you don't even have to wait, you can just do it.

So, where is your mind? Is it inside you, or outside you, or somehow "elsewhere"? At least visually, our mind's show includes a reasonably well defined spatial background, and so does our tactile sense and sense of hearing, though somewhat less precise. Do all those spaces occupy a location or are they completely disconnected from the material world in which our bodies are located?

It is not at all clear whether these questions are even meaningful. Yet we have a strongly ingrained sense of our mind being "inside" our body and the material world being mostly "outside" our body. This orientation is baked into our language. When trying to explore our mind, we typically use the word introspection. The word extrospection is less often used but can be found in dictionaries; it means exploring what is outside you, in the world around you.

This usage, however, is very misleading. It invites us to look through the wrong end of the body-mind telescope.

Our empirical view turned inside-out and outside-in

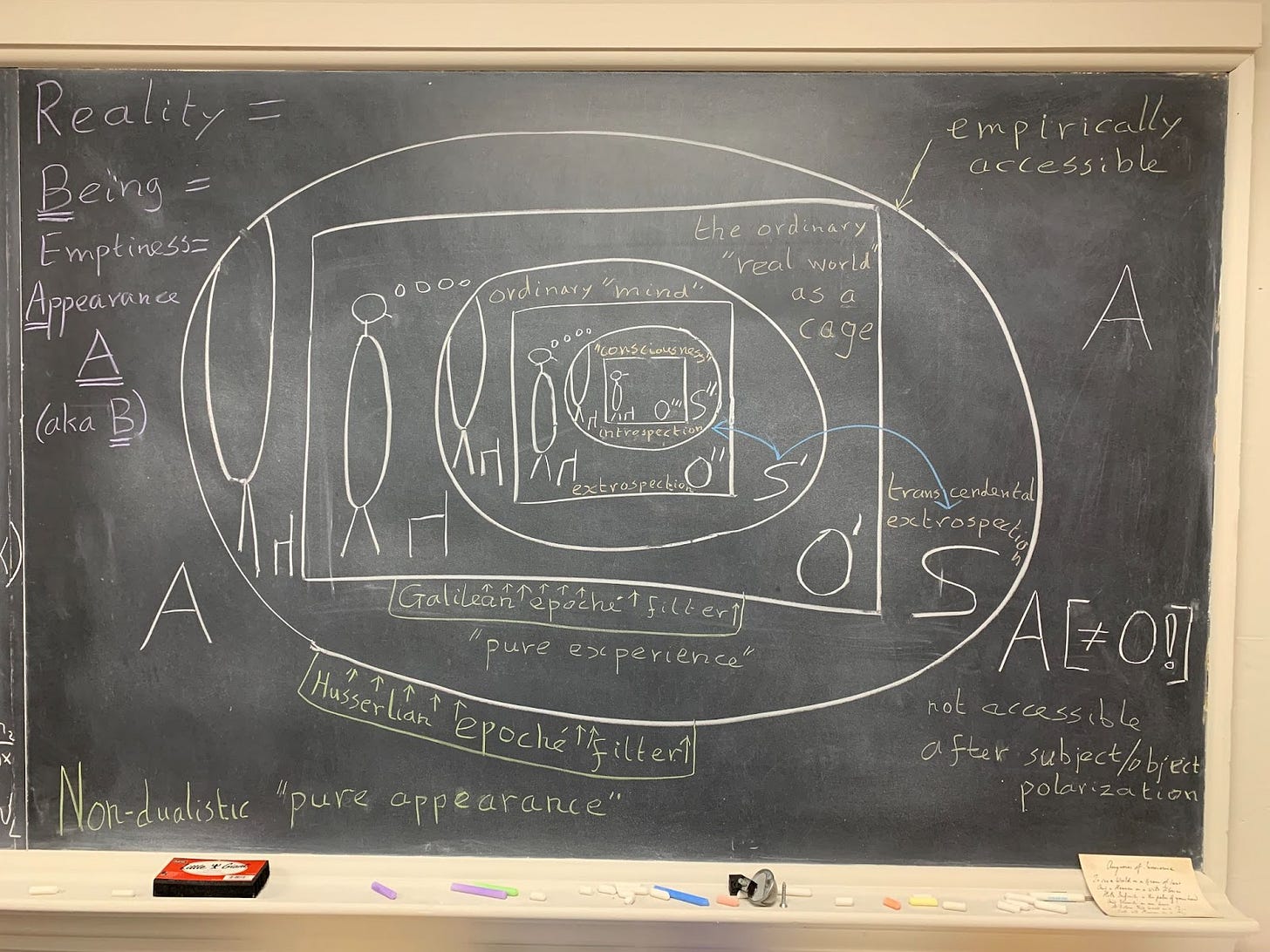

Already in entry #016, we saw in the NYT diagram that, empirically speaking, our actual mind S contains the material world O', which in turn contains our *sense* of mind S' associated with brain and body. And in entry #018, in Fig. 51, the blackboard diagram reproduced below, we saw that the map of our mind, S", which we use to communicate with others, is contained in the map of our world, O", which itself is contained in S'.

When we directly experience the world in a first-person way, we experience O'. When we talk about the world with someone else, each of us uses our own map O" as a communication device to describe what O' looks like to us. Therefore, when we experience how everything, including ourselves, is part of the Universe, it is O' that we "have in mind" as the Universe O', including the "ordinary" everyday world, labeled as such in Fig. 51. And when we locate our "ordinary" sense of mind, S', we do so in or near our body, which in turn is located within the "ordinary" world O'.

So far our first-person experience. When we *talk* with others, in second-person mode, we descend one more level toward the center of the diagram. There, our body representation on the map within O" is shown to the left and slightly upwards of the 'e' in extrospection. If we talk with our friend about our mind, we are dealing with S" as the representation of our mind. And if we describe that we are getting into meditation, we are likely to use the expression "introspection", since from the description of the world O" we move "inward" towards S". In contrast, the chair in front of us is something we find by extrospection, as indicated in the diagram.

The remarkable thing is that our actual mind S, the stage on which all dramas of our ordinary life play out, is the most "outward" of all the realms that we have been talking about so far, even though we call a study of the mind "introspection." This is the most dramatic way I can think of, to depict how we label the use of our life's empirical telescope the wrong way. We look inside our mind to the "outside" world in all its empirical stages; conversely, we look outside to what we consider to be our "inner" world.

Looking ahead

In the previous entry, #018, we explored the logistics of the blackboard diagram, and now we are exploring the look-and-feel of the different realms. The current entry is the last one in Part 3 of the FEST log. In Part 4 we will continue to explore this diagram, since there still is a lot to say about the nature of, and the relationships between, the outer three realms A, S, and O'. In parallel to that exploration, we will build up a very different type of diagram, which I have already announced as the double diamond diagram, one that is more abstract but covers essentially the same ground.

As for now, let me briefly sketch how I see the outer three realms from a contemplative point of view. How we can then make contact with a scientific point of view is still a wide-open question. Only after we start developing a science of mind, do we have a fighting chance to answer that question, with a double pronged attack. By using the phenomenology of matter and mind as a road toward developing a science based on those two empirical phenomenologies, we can follow the same path that natural science has explored: starting with observations, and carefully building and testing adequate theories to go with those (in contemplative terms: starting with practice and carefully developing a view).

Another quick sneak preview

Here is a bare summary, starting with a sneak preview of Part 4. S can be seen as Plato's cave, while A is the world outside the cave. Alternatively, A is a paradise from which humans risk being expelled, in an atemporal way, by a "fall" into a subject-object duality, moment to moment.

Inside that cave, a second "fall" can be made into a cage where the notion of "pure experience" is forgotten, and our sense of our own mind shrinks further from S to S'. Not only have we lost our sense of the openness of a nondual worldview, "pure appearance", but even the sense of "pure experience" has been lost.

The cage could be labeled "Galileo's cage", but that would not be fair since he saw the world as composed of mathematics, which he considered the language of God's thought. For him, the cage had an open door to God in a (neo-)Platonic way. Science gradually lost sight of that door, and in the last century found itself locked in that cage.

While continuing with our experiments in entry #004, we will discover that Husserl's cave is a deluxe version of Plato's cave; as we will see, of a transcendental kind, but still a cave. And while continuing with our experiments in entry #005, we will see how Nishida found a ladder leading out of the cave, but wasn't yet quite sure how to use it in the context of philosophy, though deeply inspired by Zen Buddhism.

A new experiment: subject-object reversal

Our last experiment was presented in entry #005, "Experiment 1+2): matter as experience as appearance", the last entry of Part 1. All of Part 2 was dedicated to comparing theories in the science of matter and the science of mind. So far, part 3 has followed the same pattern, but with the addition of contemplation, and especially nondual contemplation, as input material for theory formation.

But now, finally, we will get back to the lab, our own mind in the case of a science of mind. In entry #005 our latest experiment was numbered 2), and after that we combined it with an earlier experiment, numbered 1), to make the combined experiment "1 + 2)". Continuing the numbering scheme, we proceed to get:

Experiment 3. Subject-object reversal

Here we will experiment with our ordinary attitude, in which we play the central role of a self or subject in a world in which everything else plays the role of objects. The instructions are very simple. Look at an object, perhaps a tree. First spend a minute or so watching the tree, while becoming aware of the way that you are actively doing the looking, whereas the tree is something that is looked at.

After a minute, switch roles. Let the tree look at you for the next minute or so. At first you may not know how to do that, but don't worry about details. Just let yourself be seen by the tree, in whatever way that feels natural. You simply give the tree an active role of a looker, and you yourself take on the more passive role of somebody being looked at by a tree.

I suggest you repeat this a few times, at different times and in different places, with different trees. You can also perform the s/o reversal experiment, to use an abbreviated term, with different objects. However, if you change all the aspects of an experiment all at once, it may be more difficult to notice a relationship between what you are changing and the way you experience the same experiment at different times and places.

Before reading any further, I strongly suggest that you try this experiment for yourself a few times. You have only one chance to explore this experiment afresh, approaching the experiment with minimal prejudice, before reading the following comments.

Many possible outcomes of this experiment

In my experience, and in that of many others whom I have suggested to do this experiment over the years and decades, in the vast majority of cases people very quickly notice surprisingly vivid reactions, which can take many forms. It is a bit unfortunate that I have to write this, because it is more natural to introduce a new experiment of this type without saying anything about what to expect, and let it all unfold in real time. Alas, that is difficult to do in book form.

One surprise for many is that putting yourself in the role of an object can easily change feelings in your own embodiment. We all know how a sense of being looked at can change our physical sensations of being present in a situation. What is unexpected is the extent to which this also happens, in a variety of ways, when playing with the notion of a tree looking at you.

And I have to add immediately: there is a minority of cases in which someone reports that there is nothing to report. Whenever that happens in a group, it is then an equally large surprise for those who did find some clear effects, as it is for the person who did not notice anything to report. And it has the extra advantage to challenge those who clearly felt something to find more precise ways to report what they found.

I will stop here, for now at least, and invite you to play with this experiment in various ways. If you can find one or more others to join you in a small group, to get more data and more angles on experience, so much the better, as I also suggested already for the earlier experiments in entries #004 and #005.

I don't know the historical source of the s/o reversal experiment. It is quite likely that it goes back a long time, perhaps at first in oral traditions for contemplative training. I personally came across the suggestion when I read it in 1980 in the book "Time, Space and Knowledge: A New Vision of Reality" by Tarthang Tulku (Dharma Publishing, 1977), where it was listed amidst several dozen other exercises as they were called. The book is also interesting for what I would call theory, in addition to the various experiments described therein.

It was this experiment that I found most useful, for myself and for many others, in that it had the most rapid effect in turning up new aspects of our own mind. At least for most of us, it seems completely novel, notwithstanding the simplicity of execution. Since I discovered this experiment, when I am asked how many weeks or months you have to practice meditation before you can see a clear effect, I give them this experiment, if possible in person. They then typically see an effect within minutes to their (and my original) surprise. As such, it is a good candidate for starting a short course in the experimental science of mind.