A call for innovation

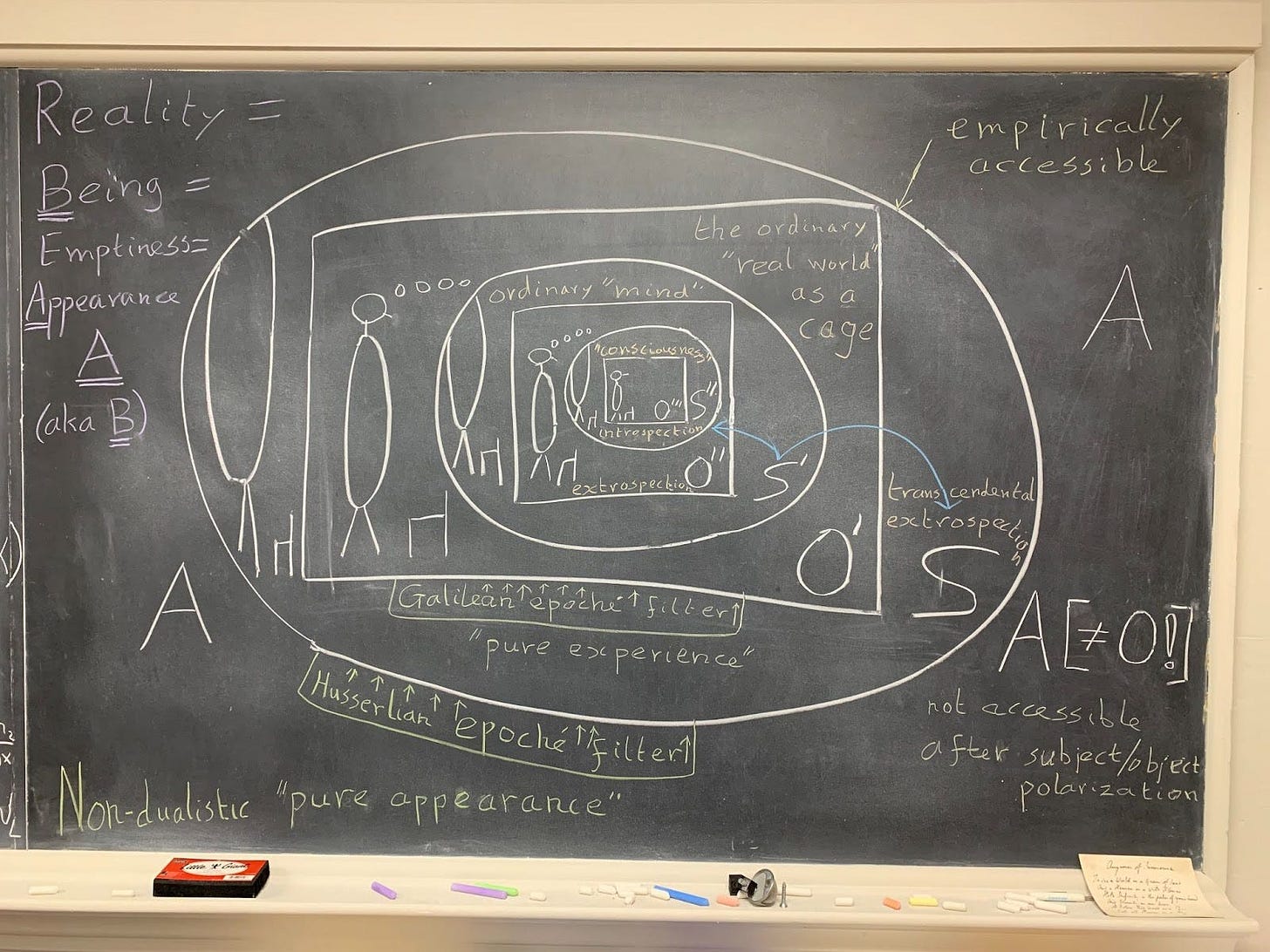

We all learn a bit of human anatomy in elementary school, like the fact that we have a heart and lungs and a brain. Well before elementary school, children can already sketch arms and legs, even if only in the most rudimentary way as stick figures (and some physicists don't even bother to grow out of that level, as you saw in my publication in entry #016). But ask any adult to name parts of the mind, chances are that they won't get much further than half a dozen or so, such as those listed on the outer circumference of Fig. 50 in the previous entry, #017, reproduced here below.

It is immediately clear that many further divisions of regions such as S, O', or S' are possible. It is also clear that in our Western culture we do not have any generally agreed upon rules and systems for demarcating such divisions in the way, say, Linnaeus systematically named species of plants and animals. In contrast, a tradition such as Buddhism has developed, over almost two thousand years, its Abhidharma system, containing highly detailed inventories of reality, encompassing both matter and mind aspects. For a recent, very readable book introducing Abhidharma in the context of Yogachara, see "Making Sense of Mind Only" by William Waldron.

Even so, my definition of science —whether focused on matter, mind, or both, as I sketched in entry #001 —includes universality, in particular the existence of a self-governing global community of peers. Currently there is no such global community. A system like Abhidharma may serve as the starting point for the crystallization of a universally recognized approach to a science of mind, just as Aristotelian mechanics grew out to a worldwide system of Newtonian physics. Or some other system may do so, or perhaps two or more systems will pool their insights together to form a globally accepted foundation for a science of mind.

And mind you, there is no danger whatsoever in starting with a limited framework for such a foundation. To make this very clear, I have dedicated five entries, #008 through #012, to map out the twists and turns of what physicists, during different periods between 1600 and now, considered foundations —for a while giving the impression of bedrock, only to melt away rapidly during one of the physics revolutions of the last four centuries.

Many ways to refine the S, O', S' diagram

Returning to Fig. 50, note that all of the area within the outer circle is a symbolic representation S of our own subjective mind, which includes all that we experience. One part of that mind, depicted as a rectangle in the middle, is O', the place in our mind where we store our knowledge of what we call the objective outer world, since we imagine it to be outside us. But why this map, and not others? We have so many different ways to make maps of our knowledge of the world. Any ordinary atlas shows very different maps, highlighting geographical, political, and many other aspects that might be of interest.

In everyday life we can talk about a human body or a chair as objects in that outer world. But when we put on the hat of a scientist, let us say a physicist, we find that everything around us, as well as inside our body, exists as a collection of atoms and of molecules made of atoms. In the previous entry, we saw how science provides a filter which lets through only those experiences that are relevant for a particular science, physics in our case.

Different people carry in their mind very different levels of knowledge about the nature of matter, about the richness of plants and animals populating the world, about the vastness of the Universe and the structures therein, and so on. Let us see whether we can start slowly and just go one step further in complexity.

From physics to biology and beyond

If we want to study biology for example, instead of physics, we have to apply a filter that lets through higher-level concepts, compared to atoms and molecules. In particular, we must be able to recognize cells, and more generally, we have to start with recognizing the difference between living and non-living systems. Where physicists see both of these systems as made of atoms, biologists see a sharp distinction between the two.

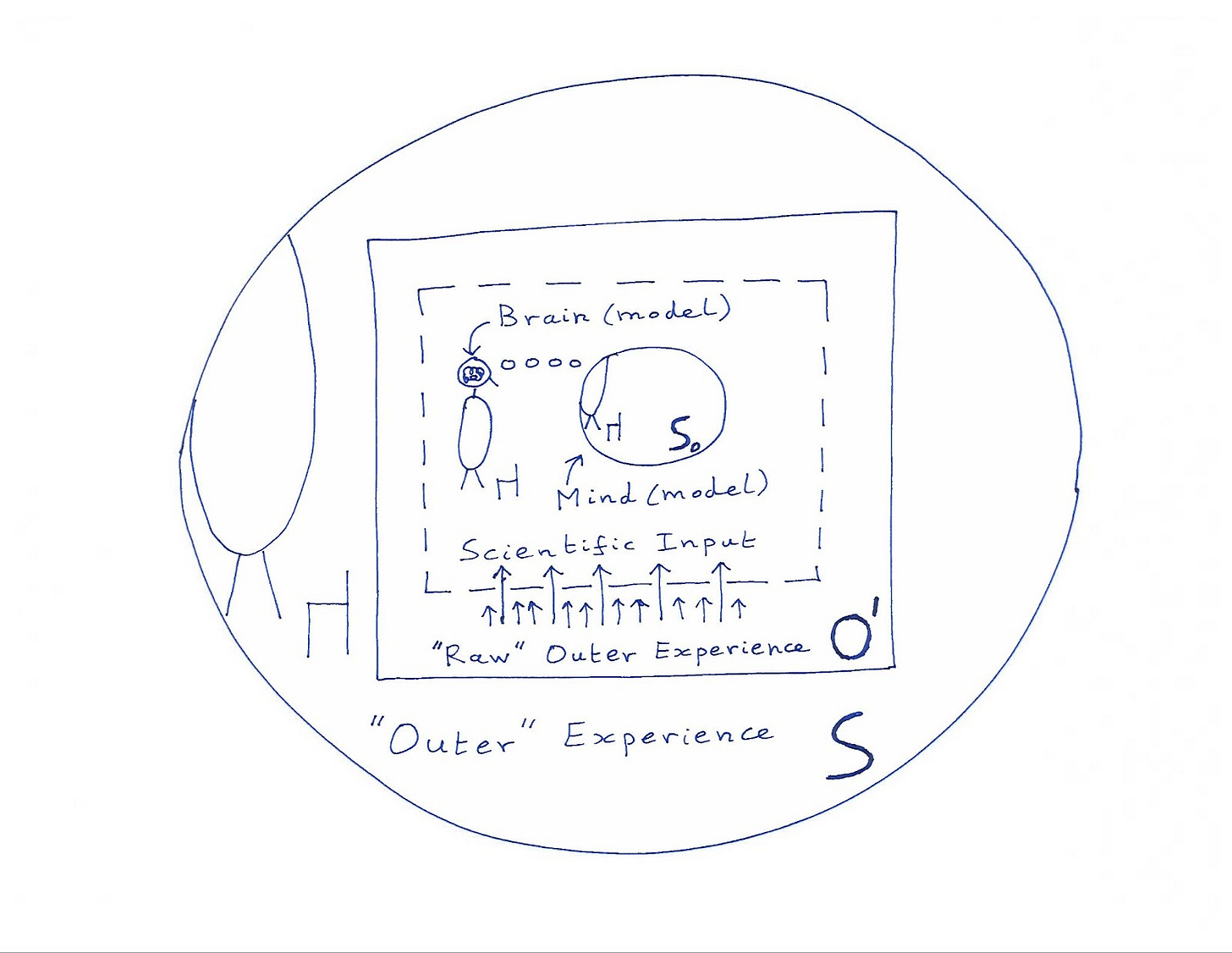

Fig. 52 indicates the way in which a neuroscientist may see the brain, and the way a cognitive psychologist may see the mind. The kind of information filtered out is rather different from what was filtered out in Fig. 50. As a result the scientific description of the world, the part of O' inside the rectangular dashes, no longer contains atoms as fundamental building blocks, but cells and in particular the network of neurons and other cells in the brain.

In Fig. 52 the outermost part of S, labeled in Fig. 50 as "inner experiences", is left out, to keep things simple. Only the "outer experience" is shown, both the "perspective" part outside O' and the "objective" part inside O'. The latter is labeled as "raw" outer experience, as opposed to what makes it through the filter of science, here labeled as "scientific input".

The role of the objectified mind So

In addition to a model of the brain, Fig. 52 points to a model of the Mind, labeled here as So. This corresponds to the S' part of the original NYT article depicted in Fig. 49 in entry #016. There I introduced S' in the following paragraph:

Why don't we point in all directions away from ourselves, as "outer" as we can indicate, when asked to locate our mind? The answer is that while we are the users of our mind S, that use is so tacit and so fully transparent, that we are left no choice but to point to S', the objectified and thus reified image of S, that has been made into an object S' within the realm O' of all other experienced material objects.

In both entries #016 and #017, I discussed at greater length the difference between our actual mind S and what we usually consider our mind to be, S'. In tandem we consider our body to be the one drawn inside O', while what we can actually see is the body drawn only partly, outside the rectangle O', but of course still inside S.

Why introduce an extra notation So? I wanted to make a sharp distinction between our everyday habit of pointing to our head and specifically to our brain as the seat of our mind S', as a modern habit, and the way neuroscientists talk about the brain while having very specific models in mind (models So in their own mind S!). Speaking of S' is more of a metaphorical habit. When people say "my brain is tired" they are talking about the "raw" outer experience in O' outside the dashed rectangle, not about a model of the mind, arrived at in cognitive science in So.

Back to the blackboard diagram

At the end of the previous entry, #017, in Fig. 51 I introduced a picture that I had drawn on the blackboard in my office, half a year before I started my current FEST log. As soon as I could literally see in front of me a new direction towards creating a "map of reality", including room for matter as well as for mind, I saw that it might be possible to find a starting point for developing a science of mind.

Of course, a single picture is just a single picture, and I welcome the construction of many other inroads towards a science of mind, by others as well as myself. For example, within a few months I hope to introduce a complementary picture, what I call a "double diamond diagram", connecting Husserlian phenomenology, modern science, and contemplation. But it was my "blackboard diagram" that gave me the confidence to start writing this log in "open kitchen" style (or, for scientists, in arXiv style).

For me it served as a proof of concept. Could I return to the picture I had sketched late last century, that had been published with the implication of an exclamation mark and a question mark? An exclamation mark as a stop sign: we cannot use any empirical evidence in describing the reality of the world around us, O. And a question mark: can we say what, if anything, we could use to replace O?

As soon as I had sketched the new picture, one early morning in the fall last year, I was eager to see whether it would make any sense to others around me. As the Head of the Program in Interdisciplinary Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton for more than twenty years, many people were in the habit of stopping by in my office to inquire "what was new" or just to chat about new attempts at boundary crossing between established fields in science. I used that opportunity to see whether I could get across my main ideas in the time span of sipping a cup of coffee.

I soon found out that, yes, I could get some general idea across while the coffee was still warm, but it was also clear that in all cases many questions remained. Little did I know that I would feel obliged, a year later, to write 50,000 words, the size of a small book, just to get to the point of even showing the figure. It will probably take me another 50,000 words to go deeper into the theoretical ramifications as well as the challenge of designing corresponding experiments, of the type I started to discuss already in entries #003 through #005.

The realm of appearance, A

In the original NYT article, Fig. 49, the background was labeled O, short for the objective reality which we normally assume to be the world we live in. It stretches out from the space near us to the edge of the observable Universe, and back in time to the Big Bang. In that figure, I had crossed out the area O, because it is not empirically accessible. So I was left with S, the mind of an individual person, within which there is room for a representation of the world, O'.

My intention was not to doubt or argue against the reality of the world as we know it. Rather, all our experiences of the world are real experiences, and as experiences they are part of our mind, S. Within S, they are stored in the rectangle labeled O', which is our own "view of the world" and as such is private. We cannot communicate our view by sharing it in a literal way, like a "mind meld" in science fiction. When we talk about "sharing" our view we really mean mapping our very rich and detailed personal mind content onto a reduced "map" that we can then pass on to others in the form of a description. That "map" lives also in O', but we consider it to be within our mind S', where it can be labeled as O", even further removed from O. This is spelled out in further detail towards the end of this entry where we will come back to the O, O', O" conundrum in Fig. 18, which will be replaced by A, O', O".

The reason to suggest A, appearance, as a more accurate replacement for the material world O, was that I had started to play with the kinds of experiments that I reported already back in entries #003 through #005. There I described how we can train ourselves to see matter more empirically as our experience of matter. And following that, we can describe experience even more precisely as the appearance of the elements of experience, namely subject, object and their interplay. These are the three elements typically present in any experience: the experiencer, what is experienced and the experiencing that connects the two.

Starting with A, my best attempt to point to the nature of reality, is what led me to the title of the current entry: "A Mind in a World in a Mind in Reality". Or a bit longer: "Our ordinary mind S’ in our ordinary world O', as seen in our actual mind S embedded in Reality A," an idea I tried to express in Fig. 51.

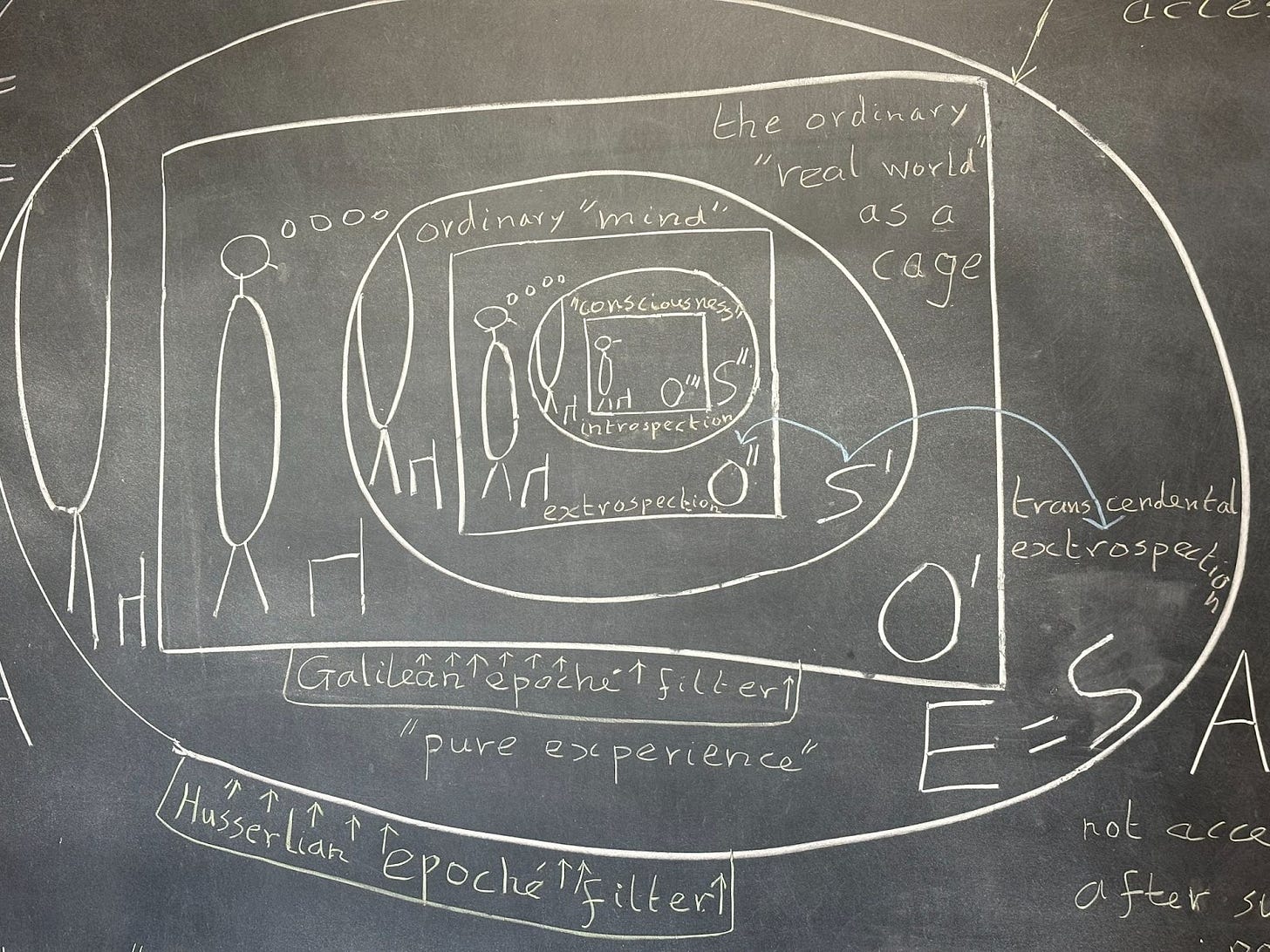

This is not the place to go into more detail. Several future entries will be needed to delve further into these matters. Instead, let me wrap up with a quick tour across the various nested domains in Fig. 51.

The realm of the mind, S

We will start at A, the background of the blackboard picture, marked at the outside of the picture. Note that in the nesting in the blackboard picture, like in the original NYT diagram, every realm includes all the subrealms that are shown within its perimeter. For example, S here includes O', S', O", etc. all the way in. Similarly O', too, includes S', O", etc.

Moving inwards from the outskirts of the picture, the first structure we encounter is S, the mind of a single person. Since each of us has a mind, it feels natural to write about "our mind", though I mean "for each of us, the mind that we happen to have". Fig. 53 shows a somewhat enlarged snapshot.

Most, if not all, of the time we are awake we focus on objects in our mind, either "inner" or "outer" experiences, without paying attention to our mind itself as the background space. As a result we fall back on our mental representation of "outer" objects within the world O', where we show up with a body, and similarly for "inner" objects within our mind S', the counterpart of our body in O'.

Realizing how much we tend to lead a life in the shadows while neglecting our own mind can be quite dramatic, especially the first time that we stumble onto that kind of insight. I have quoted Husserl in entry #004 as describing the experience that we live in experience as a kind of conversion experience.

Not only is the world O literally speaking a fiction, an idea that we carry in our mind, also we tend to completely misplace it, outside rather than inside our mind, where it shows up as O'. And, what is more, our mind, S, which *is* empirically accessible, we ignore! Clinging to what is not accessible, and ignoring what is accessible, for most of our life, until it hits us, if this is not shocking, then what is??

The realm of the ordinary world, O'

Within our mind S, we encounter what we tend to call "inner" and "outer" experiences, with the "outermost" corresponding to what we take to be the objective world, the one we seem to have access to, O'.

When we think about the ordinary world, we think about the Universe we live in, with our body and mind somewhere in a small corner of a truly huge stage. Only after a shocking awareness, mentioned above, can we begin to realize that not only is "the ordinary world" enclosed in our mind, there is a lot more to our mind, with all its memories, aspirations, fleeting thoughts and feelings, than the world that is also contained in it.

And finally, once we dare to entertain the working hypothesis that I have suggested above, another shock might set in, although initially milder: the awareness that our mind *might* actually be enclosed in something else, but *not* in a world, but rather in a realm of appearances. Most likely, the shock will be milder because initially we have no way of guessing what it may look or feel like, to have our mind *enclosed* into something. And of course, every metaphor can easily be quite misleading, which is why theories have to go hand in hand with experiments, something we will focus on more, from now on.

It is quite likely that we can't resist the temptation to let our attention flip back like a stretched rubber band, back to the old "true and tried" and most importantly, familiar view. But in the more rare case where we remain curious, and want to explore further, we may experience an increasingly odd sense of, not so much disorientation, but rather non-orientation. If so, a whole new terrain lies open for exploration, as a follow-up from entry #005.

The main reason for writing entries #006 through #012, mostly about physics and the mind, and #014 through the current #018, mainly about theoretical constructs for a science of mind, is to prepare a firm stage. It is on this stage that we will now explore the various realms that have been introduced here with the main goal to get familiar with the background realm, A. Whether there may be sensible ways to think and talk, and most importantly, explore even more fundamental realms than A, that has to remain an open question, at least for the time being.

The realm of the ordinary mind, S'

We are now at the point that we can respond to the question posed earlier: how can I, with my "big mind" S, ever make contact with other people? If I normally consider O' my world, and S' my "small mind" which I use to operate in the world O', with all of that enclosed in my real mind S, there seems to be no communication possible with others. I can talk with someone in O', but given that O' is fully enclosed in my mind S, who will hear me?

The answer is quite simple. For this we have to go "further out", which in our diagram means "further inwards", "further down" towards the center, to representations of representations of our world and mind.

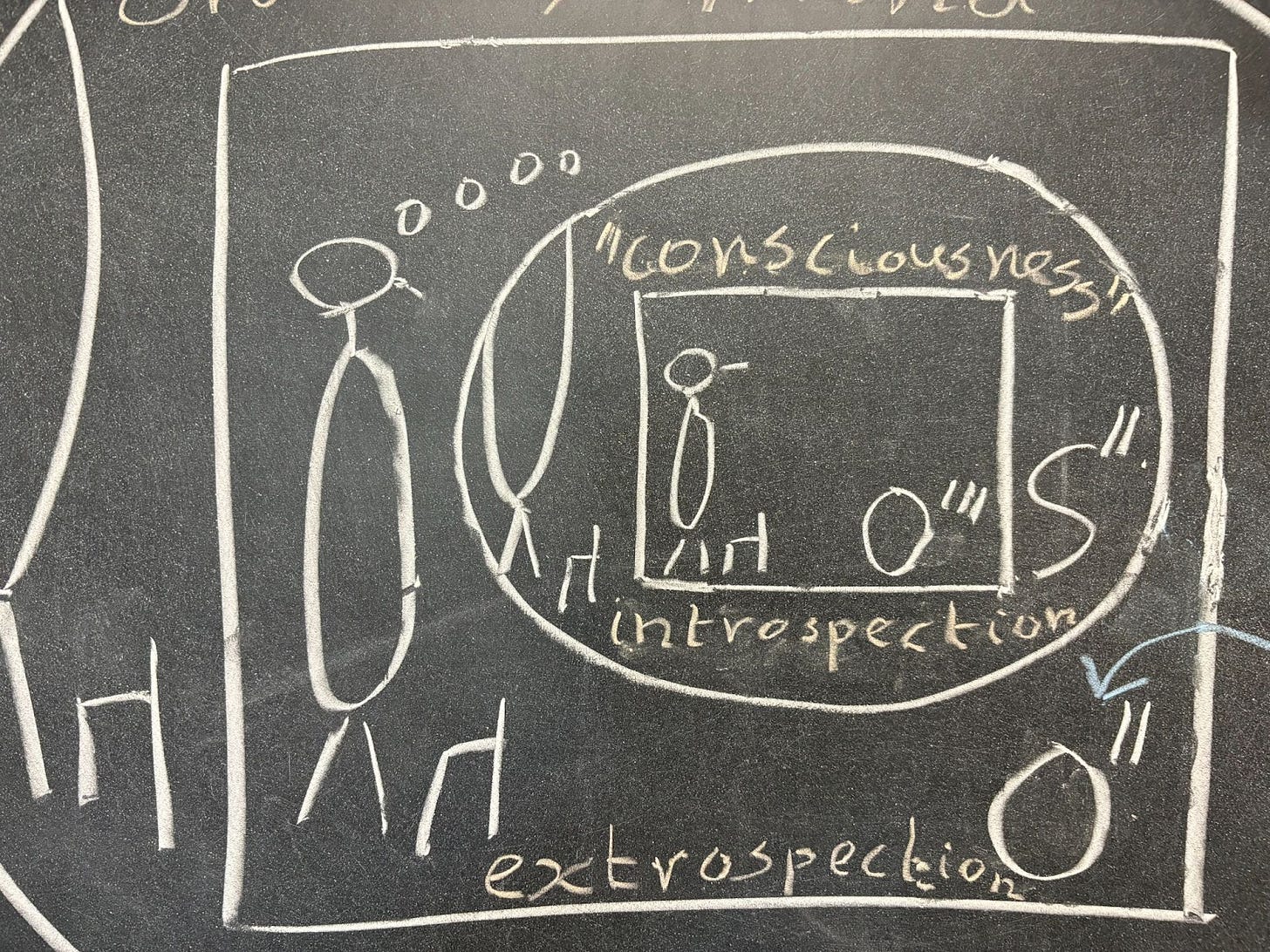

Sharing our ordinary world and mind: O" and S"

In order to tell others about our world and our mind, we have to communicate with them. To do so, we have to construct messages, such as narratives or simply gestures with mutually understood meanings. Above we already briefly discussed this question, in the section "The realm of appearance, A". But let us look at this situation in a bit more detail, using Fig. 56, an enlargement of the innermost part of the blackboard diagram, Fig. 51. In my experience the outermost part A in Fig. 51 and the innermost parts O", S" and O"' in Fig. 56 are the most difficult to familiarize oneself with.

It all goes back to the NYT diagram, Fig. 49, which allowed us to convey something about what we consider to be our real world O', and our real mind S'. The reports we can share with others are representations, elements of O" and S", one further step removed from the way that O' and S' are representations of (what we think is) the real world O and what is (indeed) our real mind S.

In this way we can communicate with others around us, by comparing our private version of the world O' with private versions of others. The way we do that is by "mapping" what we think of as our reality O', into a "map" O", which we can then communicate to others, while comparing their O" maps with our O" maps.

O" functions as a kind of virtual world, in which we can show how we experience the world, standing as we do in that world with our virtual body, our avatar, the leftmost fully drawn stick figure in Fig. 56. S" is then the mind of the avatar, a descripion of our own mind, available for others as a communication device. In that way we can even tell others how we can use our consciousness S" to describe our "reality" as our "internal" map O"'!

As an aside: when virtual worlds were developed around the turn of the century, several people remarked that sitting around a fire and telling stories, long before the use of writing, must have been the oldest form of creating virtual worlds. It is language that allows us to enter O", S" and O"' in order to share our experiences with others.

Perhaps the central take-home message of the blackboard diagram is that the outermost background realm A is formed by contemplative non-duality, while the innermost parts form the realm of language, and therefore concepts.

A little dictionary of "objective worlds"

Just for completeness and clarity, here is the logic underlying the communication description above, with the role of four different "objective world" versions, and the role that S" plays in connection them.

O is the postulated objective world, not accessible.

O' is what we normally consider to be the world.

O" is what we consider a description of the world, one that we can pass along to someone else

S" is the corresponding description of our mind, again one that we can pass along to someone else

O"' is part of the content of the mind we have just described, not the world O" that is the backdrop within the narrative, but part of the content of S" within that world, namely elements of a description of our consciousness S", if we want to communicate those to others.

Wrapping up

There are a number of other remarks written on the blackboard picture, Fig. 51, but those need to be discussed together with the continuation of the experiments that were started in entries #003 through #005. This will be the topic of the next entry, where we will start with a peek outside the realm of S to get our toes wet, so to speak, while wading into the realm of A, with an experiment called subject-object reversal.