Developing theories by tinkering with matter and mind

We encountered a bold experiment in the previous entry, #019, where we were invited to explore what it might mean to go beyond subjectivity and objectivity as we know it. I called it "subject-object reversal", and I suggested we look at a tree, first, and then let the tree look at us. I will add more elements to this experiment toward the end of the current entry.

This will be the approach we will take from now on: we will start each entry with an attempt to extend the theory side of a science of mind, followed by an attempt to extend the experimental side. The terms theory and experiment are borrowed from natural science. They correspond to what in contemplative literature is often described as view and practice.

The current entry of the FEST log is the first one in Part 4. The first Part contained a general overview of the idea of a science of mind rather than matter, with a few examples of what experiments could look like when studying our mind using our mind as a laboratory. The second Part gave an overview of the history of physics, with a number of hints of what we might learn from the meandering interactions between theory and experiment in that domain. The third Part plunged into the treasure trove of findings that were obtained in various prescientific contemplative traditions.

A quest for the unification of matter and mind

So far, all three Parts have been introductory. They have set the stage for developing a science of mind by contrasting natural science and contemplation: the currently most deeply developed sources of knowledge of the nature of matter and of the nature of mind. Having set the stage, we have no choice but to confront the central question of the nature of reality: how to approach a possible unification of the science of matter and a complementary science of mind.

The development of natural science, especially physics, initially involved disregarding the presence of the mind. For the first two centuries it seemed that physicists could get away with that omission, but one century ago quantum mechanics showed that the situation was more complex than it appeared. During that same century, biology transformed from a mainly descriptive field into a real science in its own right, with branches like neuroscience where the functions of the mind could no longer be ignored.

So let us embark on a quest for unification, that is, for finding a framework that invites developing both theories and experiments that can shed light on the way our world works — showing a material and mental side of whatever happens at any moment in our lives. We no longer have the luxury that previous generations had, up to Galileo's time, to posit a perfect heavenly realm moving by itself, in contrast to our earthly realm of imperfection and decay. Whatever we know, we know through our mind, while any mind we know comes with a body attached, so positing two separate realms is not an option.

Currently we have no clear idea how a unification of matter and mind might be realized. It could take the form of a relatively symmetric approach, similar to how electricity and magnetism were unified under the theory of electromagnetism. Or it could be that one of the two turns out to be more fundamental, with the other taking on a form of an emergent property based on the former.

Subjectivity and objectivity

We know that our sense impressions are subjective, even though we assume that there is an objective world, one that we know only through our sense impressions. Early in life, we learned how to discriminate between what we "see" subjectively and what we "see" objectively. For example, when we watch a car drive by and shrink in our view, we know the car is not really shrinking in reality. This realization is so ingrained in our daily lives that we don't pay any attention to it. We have learned not to "see" the shrinking. In fact, it would be quite a surprise if a car would pass us and then suddenly refuse to shrink. And when asked, we might say: "From my subjective point of view the car appears to shrink, but that is a mere appearance; objectively the car does not shrink."

Even though we have learned to "see" that objects don't shrink as they move away, the fact remains that empirically, "seeing" the objective fact that a car does not shrink is a two-step process. First, the visual image on our retina does shrink. Second, we then process that image in our brains to compensate for the apparent shrinkage. So the empirical evidence for the objective fact of no shrinkage is the result of two subjective operations from our side.

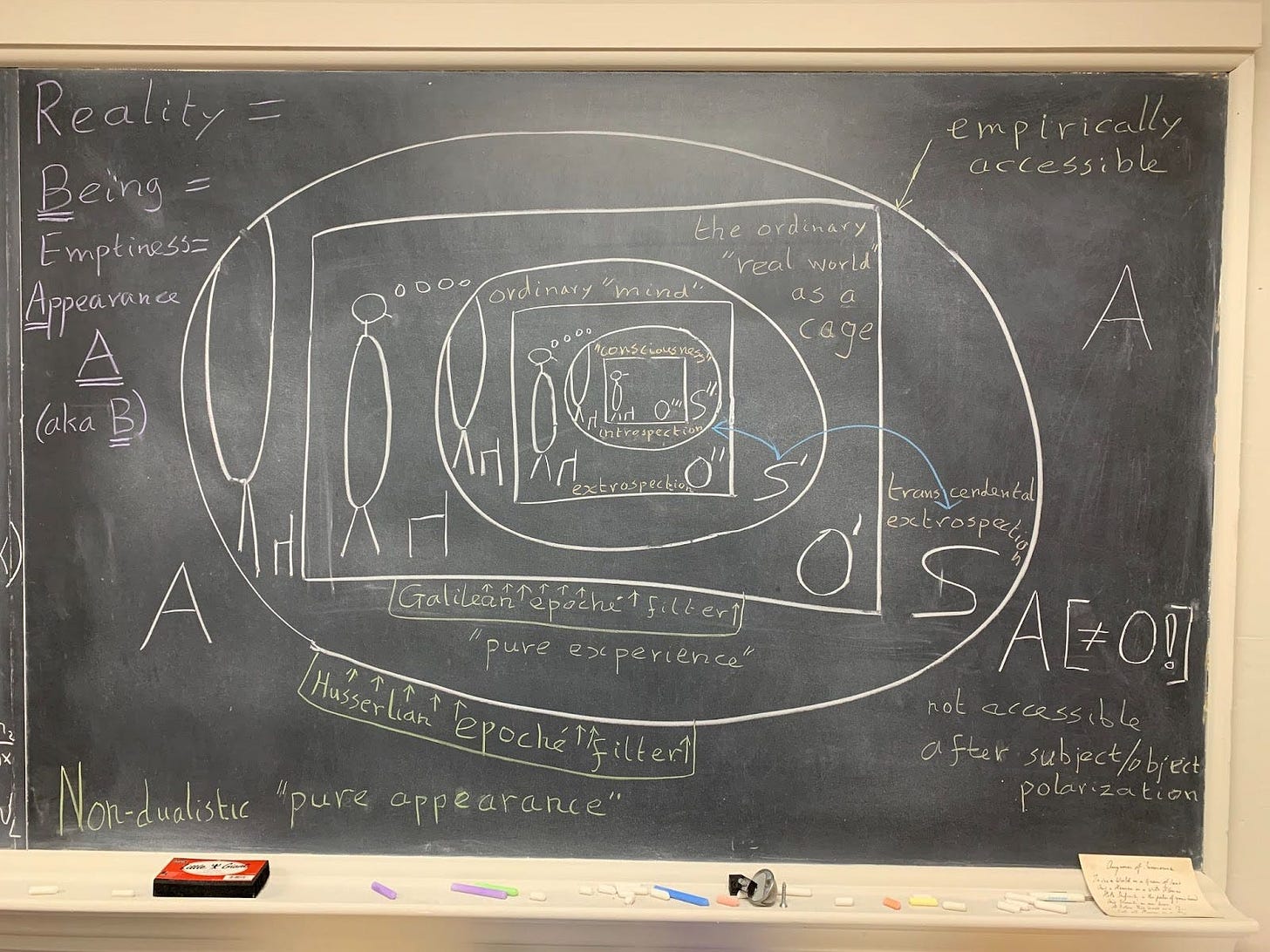

There is not, and there can never be, any direct empirical evidence that can assure us that the objective world, presented to us as processed forms of subjective observations and subjective interpretations, is really "out there," given that all the real evidence is ultimately "in our mind." We have discussed this conclusion in #016, where we found that what we call "objective" pertains to a special compartment O' in our mind, carefully walled off and maintained there, as indicated in Figs. 48 and 49 in entry #016. Since it was published in the New York Times, we called it the NYT diagram to give it a name. There O, the postulated "objective world," was seen to be empirically inaccessible, unlike O', which we can actually use since it is part of our mind, one type of mental representation among others.

When we hear this kind of argument for the first time, we are likely to shrug and consider this as a typical philosophical argument, perhaps intellectually stimulating at best, but inconsequential for all practical purposes. We "all know" that the objective world exists, and as proof we can point to the fact that science gives us a lot of power about that objective reality. For completeness, let me summarize in just one paragraph what has been a leading argument throughout the first three Parts.

For many cultures the idea of an objective reality, described most fundamentally by physics and other fields within natural science, would seem to miss out the most important aspects of being human. For that reason alone, it makes sense to critically look at how and why we tend to be so sure that matter and energy, distributed in space and time, are the ultimately real components of reality. Why do we delegate mind to a kind of side effect of the play of interacting quanta of energy (up to a century ago, it was like a clockwork mechanism, and who knows what it will be in the future)? As we have seen, from entry #000 onwards, there is plenty of reason to have a new critical look at the materialist dogmas of our time.

Replacing the mythological O with sheer appearance A

In entry #017 we fast-forwarded 27 years, and we saw in the blackboard diagram in Fig. 51 a possible alternative to the NYT diagram, in which the objective world O was replaced by a realm of appearance A. More precisely, A is a placeholder for what may be underlying experience, a *sheer* appearance that we encountered as an idea already in entry #003. Experience typically comes in a tripartite structure: there is a subject, connected through interactions with various objects.

In contrast, appearance is a more general notion, not requiring any such structure.

Simply put, appearance appears but experience doesn't experience. And central in many of the deeper insights from contemplative traditions is what is often called non-duality of subject and object, where neither of those two are considered ultimately real.

In both the NYT and the blackboard diagrams, S signifies our actual mind, while S' signifies what we generally mean when we talk about "our mind," as we have discussed at length, starting with entry #016.

An example of a non-dualistic interpretation in Islam

Buddhism is often associated with non-duality, as are various traditions within Hinduism. In Christianity, too, some contemplatives like Meister Eckhart are often considered to adhere to forms of non-duality; parallels with Zen Buddhism, for example, have been noted by the Japanese philosopher D.T. Suzuki. Since Christian theology has tended to deemphasize non-duality, and especially so in the last few centuries, I expect that a new generation of theologians will reinpret many of the older views of saints. The views of a contemplative like Saint Francis, for example, are now recognized as sharing many elements with non-dual aspects of the way Taoists view Nature.

Within Islam, I recently found a very helpful quote about Sufism. Below I give a one-page long quote from the book "Creation and the Timeless Order of Things" by Toshihiko Izutsu, a Japanese scholar of Islamic studies and comparative religion. [As for Izutsu's scholarship as well as authenticity, here is an impression: https://www.ibraaz.org/essays/119].

When I started reading it over Christmas of 2024, I was amazed to see how close his description of an Islamic contemplative's view came to the interface between the regions S and A in Fig. 51. The name of the contemplative is Ayn al-Qudat al-Hamadani [for a quick impression, cf. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ayn_al-Quzat_Hamadani].

Borderline experiences: tidal waters between A and S

[begin quote]

What characterizes Hamadání's pattern of thinking in a most striking manner is that his thought is structured in reference to two different levels of cognition at one and a same time. That is to say, the process of philosophic thinking in Hamadání is as a rule related to two levels of discourse, one referring to the domain of empirical experience based on sensation and rational interpretation, and the other referring to a totally different kind of understanding which is peculiar to the "domain beyond reason." There is admittedly nothing new in this distinction itself. For almost all mystics naturally tend to distinguish between what is accessible to sensation and reason and what lies beyond the grasp of all forms of empirical cognition. Otherwise they would not be worthy to be specifically called "mystics."

What is really characteristic of Hamadání is rather that everything -- i.e. every event, every state of affairs, or every concept which deserves being discussed in a philosophic way -- is spoken of in terms of these two essentially incompatible levels of discourse. All the major concepts that have been sanctioned by tradition as authentically Islamic, whether they be philosophic or theological, are to be discussed and elaborated on these two levels of discourse in such a manner that each of these concepts might be shown to have an entirely different inner structure as it is viewed in reference to either of the two levels.

It is noteworthy that Hamadání does not simply and lightly dispose of reason. He ascribes to reason whatever properly belongs to it. In human life reason has its important function to fulfill; it has its own proper domain in which it maintains its sovereignty. In fact, he visualizes the "domain of reason" (tawr al-`aql) and the "domain beyond reason" (tawr ward'a al-`aql) as two contiguous regions, the latter being directly consecutive to the former. This means that the last stage of the "domain of reason" is in itself the first of the "domain beyond reason". By having exhausted all the rational resources of thinking, [mystics] are able to step into the domain of trans-rational faculty of the mind.

[end quote]

[Note: In the last sentence I have added the word "mystics" which seems to have dropped out in the original typesetting, although I could also have added the word "we", which I'm sure Izutsu would have been equally happy with.]

Is it possible to go beyond empirical studies?

At first blush, Izutsu's descriptions of Hamadani's experiences don't seem to fall under the rubric of empirical studies. When Hamadani describes the transition from the "domain of reason" (S in our terminology) to the "domain beyond reason" (A in our terminology), one gets the impression that the two are not totally incompatible, like night and day. Rather, "the last stage of the "domain of reason" is in itself the first of the "domain beyond reason".

This way of speaking sounds rather familiar. Where have we encountered such descriptions before? We don't have to look very far. A large fraction of Part 2 of the FEST log you are currently reading describes the quandary that physics got into in 1925, and so far hasn't really gotten out of yet. Especially the question of how to connect the realm where classical physics dominates and the realm where quantum physics is necessary has a rather similar character.

At first it seemed that quantum physics was forced to throw overboard one keystone of classical physics after another, keystones that had been sacrosanct for more than two centuries after Newton. The biggest of those was the strict reproducibility of experiments. In quantum physics, a single experiment typically cannot be repeated, since the outcome of any quantum experiment has a large uncertainty. Only the average results from many identical experiments can be made arbitrarily small.

To put it succinctly: before 1925, empirical meant not only based on experience (as indicated by the etymology of the word), but also based on reason, on a rational interpretation that required literal and strict reproducibility of identical experiments. However, after 1925 physicists were forced to drop that extra clause required for empirical results, the classical dogma that seemed so reasonable (literally!), but that turned out to be incorrect. It definitely seemed unreasonable that identical experiments give different results. But given that experiments form the absolute foundation of science, physicists had no choice but to incorporate seemingly totally unreasonable ideas into their theories. In other words, to provide continuity in experimentation, it seems inescapable to redefine the word "empirical".

Changing the goalposts in physics

The upshot is that we still consider physics to be an empirical science. But in doing so, we were forced to change the goalposts: "strictly reproducible" became "statistically reproducible." While the quantum mechanics revolution was the most extreme case, during the few hundred years since Newton formulated his classical theory of mechanics, there have been other cases, not quite as dramatic, but still quite shocking.

Until Einstein formulated his theory of special relativity, classical physics was based on the conservation of mass and the conservation of energy, which were considered to be two separate conservation laws. Chemical reactions could change the nature of a piece of matter, but not the total mass of matter involved in such reactions. Similarly, heat energy in a steam engine could be partly changed into energy of motion, but the total amount of energy would remain the same.

Another example of changing the goalposts to make room for a new and more accurate theory occurred when Einstein found that energy and mass could be converted into each other. It was clear that neither mass nor energy was conserved. But when mass is transformed into energy, as happens in the core of the Sun, generating its heat, the *sum* of energy and mass (the latter multiplied by the squared of the velocity of light) *does* remain the same.

Changing the goalposts in a science of mind

Given the example of physics, it is only natural to look for places in a science of mind, where we could be similarly forced to shift its initial goalposts. And we don't have to look very far. There was a good reason to introduce the philosopher Husserl in entry #004, and the philosopher Nishida in entry #005, since Nishida changed the goalposts of Husserl's phenomenology.

Husserl was still empirical in what we might call a "classical" kind of way. For him experience was the foundation of phenomenology, where every experience had a subject pole and an object pole (for the cognoscenti: strictly speaking his transcendental subject plays the role of a "dative of manifestation", for whom phenomena appear, and as such is not a purely non-dual appearance).

For Nishida that was no longer the case. As we saw in entry #005, his view was: we tend to say "I have an experience", but it is more accurate to say "Experience has me". Let us look carefully at this short but pathbreaking sentence.

What Nishida called "experience" was not something that connects a subject with an object in the standard way. In giving up "I have an experience", a phrase in which a person is the subject, and instead adapting "Experience has me", a phrase in which that person is no longer the subject, what just happened? There is no new subject appearing on the scene. "Experience" cannot be seen as a subject, at least not in any standard way; it cannot play the role that already is assigned to the "experiencer". If experience is not the subject, the "me" above cannot be a proper object. Yet a sense of me appears. This can give a hint as to show how appearances can be seen as more fundamental than experiences.

In entry #004, we revisited the concept of S, which represents the total sum of experiences within an individual mind, a la Husserl. In entry #005, we introduced Nishida as a bridge that allows us to venture beyond S into A, which serves as the background "space" or "field" for the kind of non-duality that all major contemplative traditions talk about, in one way or another. By going beyond the European view of experience as centrally involving a subject, Nishida went beyond the classical definition of empirical research. Interestingly, in doing so he introduced a non-classical definition of "pure experience" in which there was no longer a central role for the subject. It was his way of changing the goalposts of European philosophy, up to and including Husserl.

Note that my interest in parallels with quantum mechanics has nothing to do with looking for quantum *effects* in the brain, but rather for quantum *analogies* in the mind. My comparisons above between the nature of the quantum revolution in matter and the nature of non-dualism in the mind, are certainly not perfect analogies. My hope is that at least they may form a first step pointing to similarities between two equally painful processes. In the domain of matter, the painful process for physicists was having to give up their so successful classical mechanics as the Newtonian "deepest truth". In the domain of mind, the painful process for philosophers was having to give up their so successful Cartesian "deepest truth" of subject-object duality.

Quantum mechanics will undoubtedly play some role or other in the nano-scale processes in the brain, like it does on all processes of that size, but that's not my point. What quantum mechanics teaches us goes well beyond physics. In general, when scientists declare that they are "absolutely certain" of something, like the "fact" that the material world is like a clockwork, it would be better to read such statements as "until now, there has been overwhelming evidence that, on the scale and under the conditions of experiments so far, a model like a that of a clockwork has given us a very good approximation of phenomena that are encountered in reality". Such an authentic way of adhering to the principle of using working hypotheses, rather than dogmas, would have made the quantum transition in physics decidedly less painful.

Nishida's tidal waters at the A/S interface

Below I am providing one more rather lengthy quote to illuminate in a concrete way how Nishida handled the tidal waters between A and S. My quote is taken from a recent unpublished manuscript by John Maraldo. He is the author of a 3-volume series, "Japanese Philosophy in the Making" (Chisokudō Publications, 2023), the first volume of which is "Crossing Paths with Nishida." Here is the excerpt, with permission from John Maraldo.

[begin quote]

Nishida’s writings can be frustrating for their lack of concrete examples, and refreshing for their power of integration.

This self in act [the subject] cannot be grasped as an object. Our awareness is active even while we would try to grasp it as if it were some thing, some object, in the world. From this active center, each of us can assume a standpoint, take a position or have a perspective on things and take account of them. But then Nishida adds a remark that turns our head around: what we call the self has to be understood from the standpoint of the world; it is not a matter of proceeding from the self, but of proceeding from the world.

Practicing physicians can say of themselves, "I went to such and such a school, I’ve treated so and so many patients and contributed such and such to the field of medicine." This description represents the standpoint of the self. Now imagine another, more reciprocal description one could give. "The world of medicine has entered into me, shaped who I have become and what I have done, and my practices in turn have changed that world." This way of putting it represents a standpoint that "proceeds from a world."

Unlike Descartes, Nishida understands self as embodied, conditioned by the world but also creative of it; there’s no such thing as an "external world."

Nishida typically refuses to separate what modern philosophy posits as two-fold: the subjective side of experience and the objective side of reality, so the primary meaning of world for him is the lived, concrete whole that provides the context of experiential reality.

[end quote]

A next step for subject-object reversal

As a follow-up from the s/o reversal experiment in the previous entry, #019, where I suggested to let a tree look at you, here is an extension. Instead of letting one object look at you, let everything in your field of vision look at you, simultaneously. It may be easiest to perform this experiment in a place without other people, who might actually happen to look at you. But after some practice, you may be able to do this equally well in a crowded place somewhere in a city. How does this feel? Is it qualitatively different from letting a tree look at you? Or is it similar but perhaps in a way such that the effect feels more strongly (or more weakly)?

Yet another follow-up is to let everything behind you, well outside your field of vision, look at you. Keep looking ahead of you, to make the experiment maximally different from the one you just did before. Does this feel different from letting everything in the whole scene in front of you look at you? How would you describe the difference?

In the next entry I will discuss these variations, as well as other ones, in more detail, together with a few descriptions of some reported outcomes.