What contains what, from an empirical point of view

So far, we have seen that all that we can possibly know about the objective world O is available to us in a reconstruction O' inside our mind S. And in turn, if we talk about our mind, assuming that it is connected with our brain, we are dealing with a reconstruction S' of our mind. We then tend to assign S' to a place in or near our body, that is, within O'. The result has been the following "Russian doll" type nesting: S' within O' within S. In the mathematical notation of inclusions of sets within other sets, this reads S'⊂O'⊂S.

It was tempting to put all of that within the objective material world O, as O⊃S⊃O'⊃S'. However, early on in entry #016, in Fig. 49, we concluded that O is a theoretical construct, strictly speaking the result of the application of an unfounded working hypothesis since, by definition, it is not empirically accessible. In contrast, S, our mind, is empirically accessible since we have defined it as the sum total of all our experiences. Therefore, O' and S', both parts of S, are also empirically accessible.

Given that every moment in our life is drenched in material and mental elements, or more than that, connected like the warp and the weft of a tapestry, there is no a priori reason to conclude that one of them underlies the other. If scientists conclude that matter underlies mind without mentioning it as a working hypothesis, then they are introducing a dogma, and while doing so, they are stepping outside the business of doing science, as I argued at the very start of this FEST Log, in entry #000.

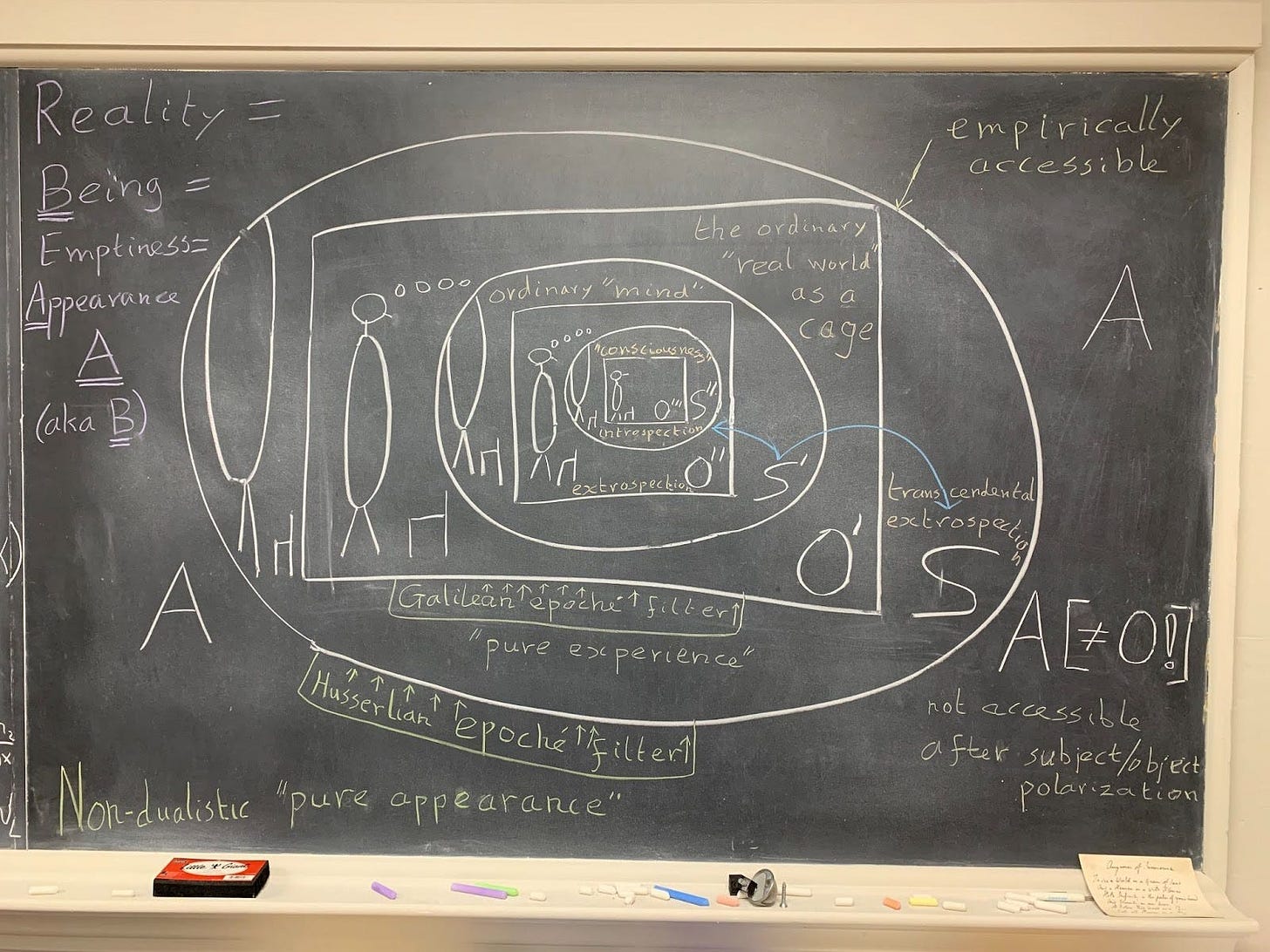

In entry #017, I introduced an alternative working hypothesis, replacing O with A, a realm of non-dual appearance. This was introduced as early as entry #003 but worked out in more detail in entries #018 and #019, the last entry of Part 3. The conclusion of Part 3 was to provide a nesting that runs from outside to inside in a one-dimensional succession as A ⊃ S ⊃ O' ⊃ S'⊃ O" ⊃ S" ⊃ . . . This nesting was sketched in some detail in Fig. 51, reproduced below.

Materialism, idealism, and non-dualism

So far, we have followed a strictly scientific way of analyzing our world. Specifically, we have allowed only the use of empirical input for our observations and experiments, in order to keep our theory honest. The immediate conclusion has been that we cannot rely on our intuition that we live in a material world. At first, this conclusion does not seem to make sense, because it does not correspond to the way we are raised in the modern world.

We all learn to view objects around us as placed outside of us, that is, outside our bodies, in the area O of Fig. 49. In other words, we have all been trained from a young age to adopt an attitude as if what we find in O' is actually "out there", in a fictitious O. We may go through a lifetime without ever considering O'; even though it becomes easy to grasp, and crystal clear, once we reflect on it. The philosopher Husserl, whom we met in entry #004, introduced the word "natural attitude" for the habit we have developed to assume we, with both our body and our mind, are part of O, the Universe we assume that we live in. Indeed, this attitude feels natural, but only because we have been exposed to this doctrine from a very young age.

To sum up, this means that in our analysis, we are confronted with two views of material objects in a material world. Throughout Part 3, we argued that O' is where we empirically experience our world, namely within our mind. In philosophical terms, this conclusion may seem to point to a form of idealism. However, it would indeed be idealism if we stopped with fig. 49, after crossing out O and leaving S as the outermost realm. In this scenario, S would stretch beyond the sheet of paper if it were printed, rather than including O.

However, in Fig. 51 in entry #017 we argued that there is a next layer or realm, A, of non-dual cognition, one that goes beyond the realism of positing O and also above the idealism of postulating that S is the be-all and end-all of reality. Both are ultimately dogmas, putting an end to empirical investigation. In contrast, A is the result of a natural extension of empiricism, as we argued in the previous entry #020 —just as quantum mechanics is the natural extension of classical mechanics, while accommodating seemingly very non-classical elements.

As a result, realism, more accurately materialism, only recognizes the realm within the area O' as real, as forming the outside, the sheet of paper as such.

A wider view is offered by idealism, which also recognizes the realm within the area S as real.

A yet wider view is offered by non-dualism, which only recognizes the realm A as real, although using the word "real" is a stretch. The notion "real" is a concept, and non-dualism reaches beyond ordinary concepts, as illustrated in the previous entry, #020, by the quote concerning the Sufi mystic Hamadani.

A burning question

This leaves us with a burning question: Is there a truly convincing way to bridge the everyday way of viewing the world we feel we live in with the scientific empirical picture that Part 3 of our FEST Log has painted —the seemingly "outer" material world O' as being given inside our mind S, and both of those arising as limited perspectives on an even wider non-dual reality?

In other words: How can we reconcile —can we really reconcile— Husserl's "natural attitude" with the perspective of contemplatives across different ages, places and cultures, who testified about a reality more fundamental than what the subject-object split of the natural attitude can offer us?

Another way to formulate the burning question above is to ask: Can we construct a "two-truths" picture of reality, a conventional or relative truth that is useful for many practical purposes, while realizing that there is a deeper truth to which the relative truth is only an approximation?

This "two-truths" notion is often associated with descriptions of the nature of reality in Buddhism, explaining how our everyday world seems to be far from perfect, while the Buddhist belief (or working hypothesis, depending on the individual) describes reality as intrinsically perfect. This attitude, however, is not restricted to Buddhism. As we saw in Izutsu's quote about Hamadani, not only does Sufism talk about a similar distinction, but just about all mystics and contemplatives adhere to comparable views.

Following that discussion, we saw that the seeming contradiction between classical mechanics, so well tested in conventional every-day circumstances, and quantum mechanics, highly accurate everywhere, also where classical mechanics fails, can be reconciled as a kind of two-truths theory.

Two two-truths theories

Under circumstances where quantum effects are smaller than the size of the error bars of measurements that are taken, classical mechanics by and large gives "true" (enough) descriptions of what is going on, while under other circumstances quantum mechanics is really necessary to describe what is being measured.

What is more, quanta have a perfection very unlike classical objects. Matt Strassler, whose marvellous book "Waves in an Impossible Sea" I have already quoted in entry #010, describes the "perfection" of electrons and other elementary particles as follows:

"This rigidity of form is why electrons and quarks and gluons, unlike rocks and stars and human beings, never get old. Age involves wear and tear, loss of integrity, damage. You can’t damage an electron; it doesn’t accumulate scuffs and scars from the buffeting that it may have experienced throughout its life of perhaps billions of years. It can’t. It remains, always, a single quantum of the electron field, period."

Isn't it fascinating? For two thousand years, Aristotle has taught us that in the realm below the Moon all is imperfect and decays, but that in the realm above the Moon everything moves in eternal harmony, without ever running out of steam. Then, for the next three centuries, from 1610, when Galileo discovered the four largest moons of Jupiter, till 1925, when quantum mechanics was discovered, all perfection was banned from our world view. But then it was reintroduced in the way the quote above described, but with a twist: in the microcosmos, rather than the macrocosmos! Who knows what will be discovered, in successive steps of deeper insight, in the remainder of this century, or later.

With this background in the sciences of mind as well as of matter, we can return to our original question, and the possibility that a "two-truths" view might help us. In Part 1 of our FEST log we had a brief encounter with experiments that showed us a way to move from seeing the world as matter, to seeing it as given in experience, to seeing it as appearing in "sheer appearance" beyond the subject-object split. In Part 2 we have discussed in some detail the two-truths aspects of physics forced upon us through quantum mechanics during the last hundred years. In Part 3, we have made contact with the two-truths aspects of contemplation. We are now ready to use the current Part 4 to address the burning question mentioned above, which will emerge in the interplay between the two philosophical concepts of epistemology and ontology.

Starting with the natural attitude in daily life

Before thinking about science or philosophy, the most natural way for us to look at the world is to recognize its material and mental aspects. If we pick up a stone, we consider the stone as material. If we recall that yesterday we picked up a stone, we can still consider yesterday's stone as material, but we can also realize that our memory of yesterday is a current mental event, the content of which is a memory of a material stone.

In philosophical terms, if we perform an ontological analysis, an analysis of what something is, we can call a stone material and a memory mental. In contrast, an epistemological analysis tells you how we can know something to be true, in our case by relying on empirical evidence.

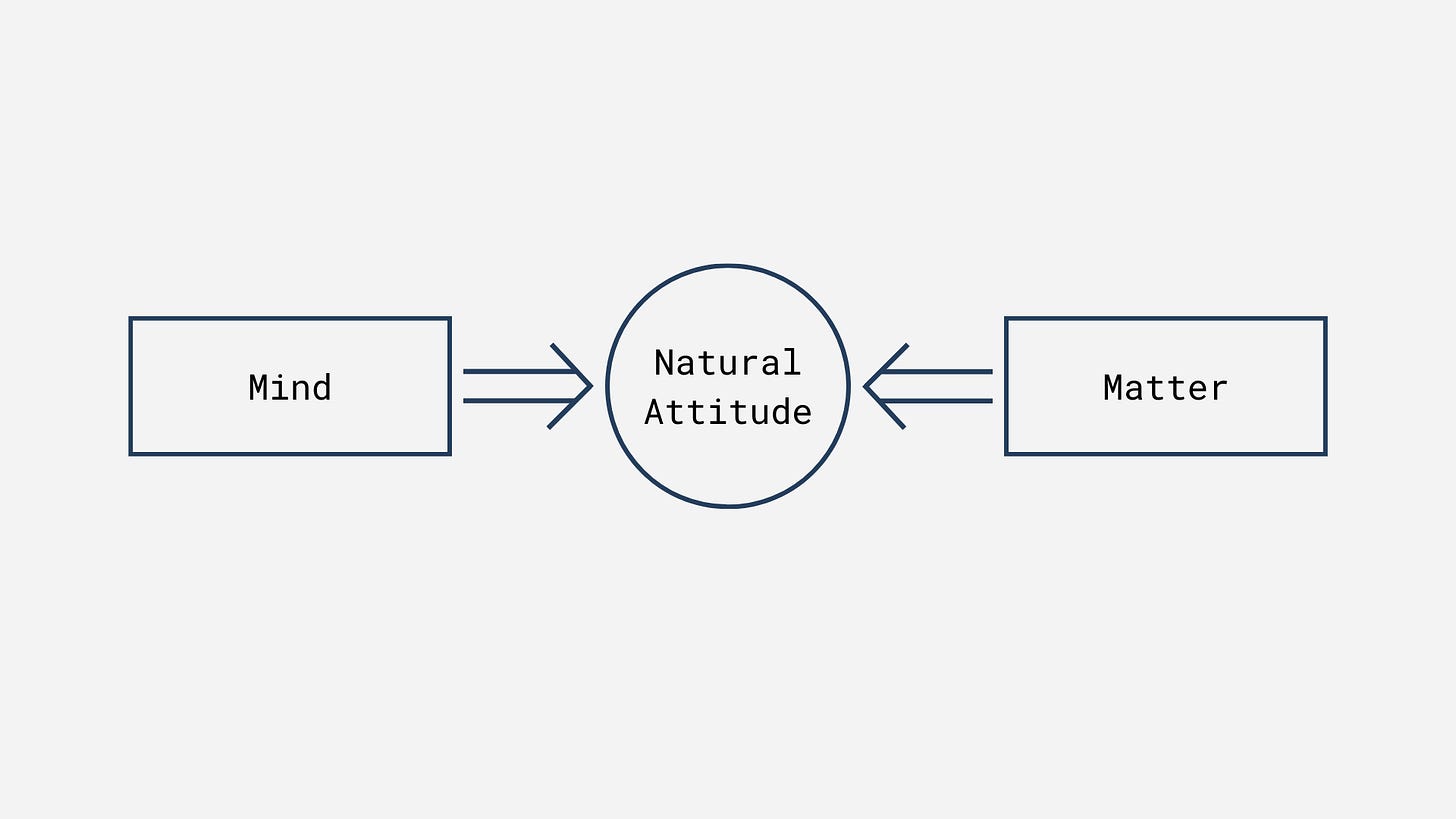

In a simple abstract picture, Fig. 57 indicates how our normal way of looking at the world recognizes the two elements of mind and matter as making up our reality.

In contrast to the ontological Fig. 57, so far in Part 3 we have only dealt with epistemological figures, from Fig. 49 in entry #016 onwards to Fig. 56 in entry #018. We now take a new starting point. We stop asking "what contains what"; does the world contain the mind or does the mind contain the world, and which mind and which world in what way, as we have done at length in Part 3. Instead, we depart from our exercise in epistemology by returning to making simple statements like "the world contains matter and mind" in an uncritical everyday way, in Fig. 57.

As a matter of bookkeeping, we should refer to Part 3. In Fig. 58 we note that the world can be seen as given by the representation O', which is embedded in our mind, S, as indicated in Fig. 59.

Finally Fig. 60 reminds us that the naive ontology of the world that we seem to live in, given in Fig. 57, is the output of a particular attitude, when analyzed epistemologically —namely the natural attitude.

Climbing out of Plato's cave: Experiment 1

Our next task is to connect the two approaches. Can we translate the nesting scheme we used in Part 3 into a corresponding scheme in our new approach, now in Part 4? This will be our first cross-classification challenge, in our budding science of mind exploration.

Given that we are modeling a science of mind on the same principles as natural science, our science of matter, let us start with the first criterion that we listed back in entry #001: "Experiments always win out over theories."

So, let us look at the very first experiment that we introduced in Part 1, in entry #003. It was "Experiment 1): the nature of matter as experience." The instruction started with: "You may see a stone. Notice how you normally view it as a chunk of matter. Now try to see the stone as an experience."

In the following entry, #004, we connected this with Husserl's epistemological method which he called the epoché. It was only in Figs. 49 above, and the far more elaborate Fig. 51 in entry #017, that we made a theoretical interpretation of what happened while conducting Experiment 1. It meant moving from the realm O' to the wider realm S, containing our world O', a move akin to climbing out of Plato's cave to realize our mind's foundational role.

A balance between mind experiments and matter experiments

While laying the foundations for a science of mind, early on in our FEST Log, we naturally introduced an experiment that moves our attention from a stone as an object to the subject experiencing the presence of a stone. Given that we started with a kind of "equal rights" exercise, in providing the World equally with material and mental elements in Fig. 57, it would be natural to introduce additional experiments that move in the opposite direction. That would mean deemphasizing the presence of a subject and focusing more on the presence of an object instead. But that is exactly what natural science has been doing already from its very beginnings in the 17th century!

In Part 1 we introduced Experiment 1, already mentioned above, and Experiment 2, discussed further below. Both of these experiments were mind-based. The first one invited experimenters to shift their focus from material objects to the way in which those objects are empirically viewed in our mind. The second one invited them to go even further, in an extended version of the notion "empirical," related to "sheer appearance".

In the current entry, we will try to fit those two mind-based experiments from Part 1 into the framework that starts with Fig. 57. In the next entry, we will restore the balance and focus on experiments in natural science, which all seem to be matter-based, according to the lore. Of course there is an inconsistency involved in applying that label, without addressing how we do the "heavy lifting" of carrying the outcomes of those experiments into human minds, enabling us to write natural science reports. Ignoring that inconsistency, we will explore whether we can find a place for matter-based experiments as well as for the two mind-based Experiments 1 and 2.

As a sneak preview, one novelty is that we will soon be able to escape the asymmetry between a science of mind and our established science of matter. In Fig. 50, in entry #017, the use of a science filter disrupted the natural nesting that we started to build up between alternating S and O symbols with increasing numbers of accents per symbol. Clearly, the sciences of mind and matter were not treated equally, with filters appearing for matter and not for mind.

The symmetry between matter and mind, which was broken in the epistemological series of diagrams in Part 3, will be restored in the current Part 4, starting in the next entry. We will do that using the built-in left-right symmetry between matter and mind in Fig. 57, which is very different from the built-in asymmetry in the use of nesting, starting in Fig. 49 in entry #017. End of preview, for now!

A translation exercise

Returning to Fig. 57, how are the three elements "World," "Mind," and "Matter" related to the earlier epistemological diagrams? Let us inspect them one at a time, starting with "World".

What is labeled "World" functions as a container for elements of the type "Mind" and elements of the type "Matter." This implies that mental events are nested within the larger realm labeled as World. There is only one way to translate "World" from the ontological Fig. 57 to an earlier epistemological figure. This is what Figs. 58 and 59 showed: "World" corresponds to O', not as something stand-alone but as a form of knowledge arising in the mind S.

Moving on to the box with the label "Matter" is straightforward: whatever we call material objects indeed can be found in O', in Fig. 49.

The only remaining question is how to handle the box labeled Mind. Since the elements from that box are located in "World," considered as O', the only representation we have available for Mind is S'. Our actual mind, encompassing the totality of all experiences, is not available in O'; rather O' is available in S. Therefore, we must conclude that we have no choice but to use the following translations from Fig. 57 to Fig. 49:

"World" -> O'

"Matter" -> O'

"Mind" -> S'

This means that our inclusion of S inside the World in Fig. 59 was premature. Yes, epistemologically S ⊃ O', but since epistemologically S ⊃ O' ⊃ S', it is S' that we are dealing with in O', the part of reality that can be experienced in the natural attitude.

This raises the question of what to do with our actual mind, S, since it just doesn't fit into the one-dimensional diagrams from Fig. 57 through Fig. 60.

A two-dimensional diagram: guidance from Experiment 1

Note that no translation is ever perfect. Since we started out with "World" as containing material as well as mental elements, it may seem odd to classify our "World" as material. Actually, that is not so much our problem. Rather, it is the problem of modern society as a whole which tends to consider matter as the basis for mind, as a kind of dogma, as already mentioned in the first section above.

We might guess that the only way to escape from that dogma is to jump out of it to a higher level in our new diagram, corresponding to what was shown as an outer level in the epistemological diagrams. This idea may sound whimsical, but let us not speculate. Instead, let us find guidance from Experiment 1, in constructing an ontological theory, following the methodology of science. This will lead us to a logical conclusion when we try to embed Experiment 1 into Fig. 57.

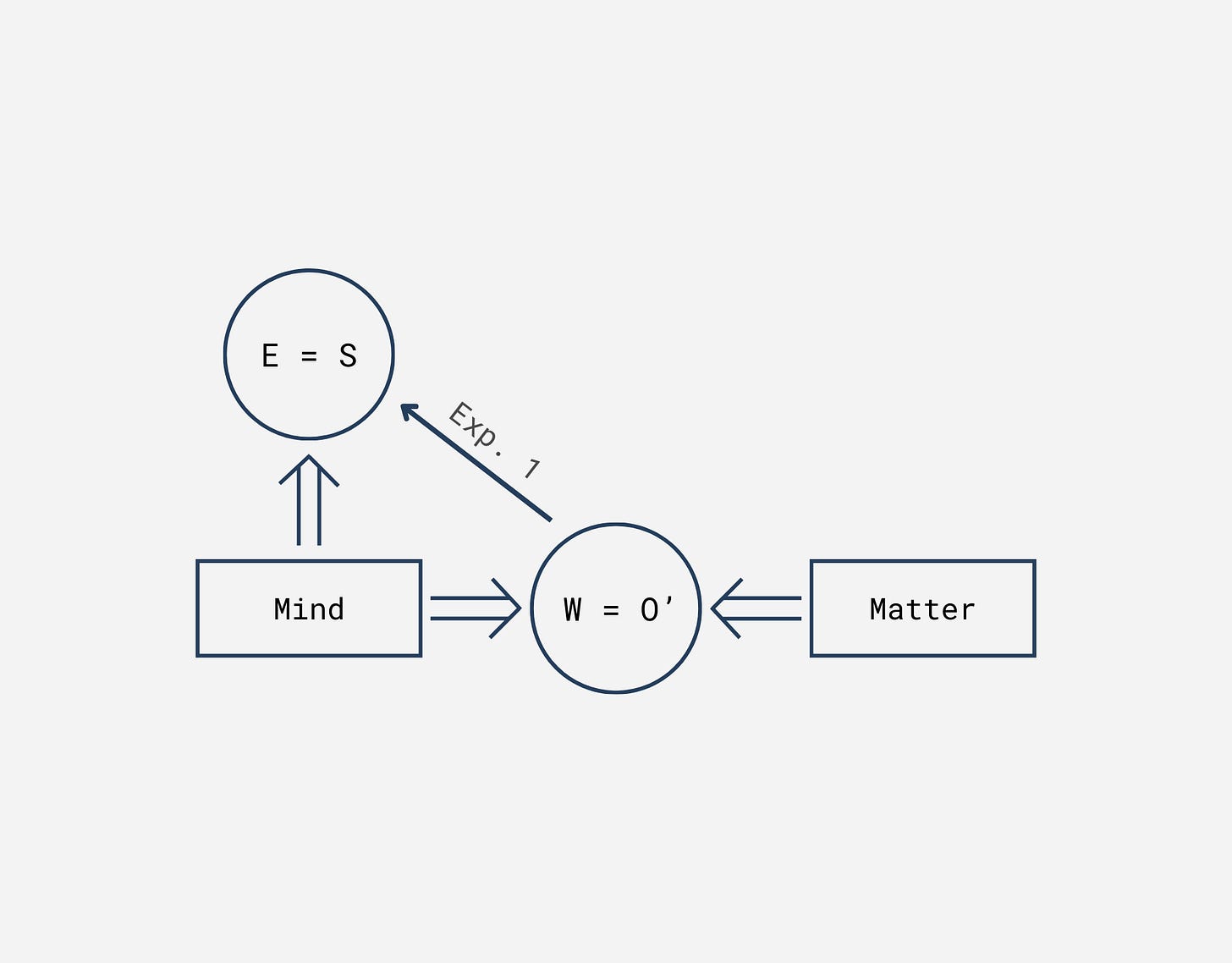

The instruction for Experiment 1 was to "try to see the stone as an experience", instead of a material object. This translates as: use your mind, as you find it in the realm S, rather than what you find in the realm S'. Since no room is left for anything like S horizontally, we may as well place it vertically above the "Mind, World, Matter" line. Moreover, since the "Mind" box, corresponding to S', is at the left, the natural place for experience is straight above "Mind" in Fig. 61.

In that figure we have shifted our perspective from the natural attitude, where a material object is just a piece of matter, to a perspective where we "see" that object as given in experience. As a result, we have transcended the limitations of the natural attitude, to explore a second dimension, above the confines of a materialistic world view.

But let us be careful, taking one step at a time. Experiment 1 showed that we can view a material object as given empirically as the experience of what we call a material object. Fig. 61 makes that explicit, as a move from living in the Natural Attitude as a habit to living in a "world of experience", a new way to view the world that in turn with some practice can become a new habit. This was discussed in entry #004, in the section "Edmund Husserl."

In Fig. 62, below, Experience E is equated with S, a label for all experiences in a mind S, as E = S. And in turn, the World W is equated with the material world O'. This follows our earlier Fig. 49, the NYT diagram. Note that in the more detailed Fig. 51, the blackboard diagram, the realm S is also labeled "pure experience", and could have been labeled E as well in the alternative notation that we have introduced here. The "pure" in "pure experience" there indicates that it is not a representation of experience, which S' is, but the real deal, the mind S itself.

From experience to appearance: guidance from Experiment 2

Encouraged by the usefulness of Experiment 1 in extending the baseline of the ontological Fig. 57, let us see what we can do with the second experiment, which appeared back in entry #005, associated with Nishida: "Experiment 2): the nature of experience as appearance." The instruction started with: "Even when you sit quietly, and your mind is relatively calm, every moment something appears: a distant sound, a fleeting thought, your breathing. Gently be aware of all those appearances appearing."

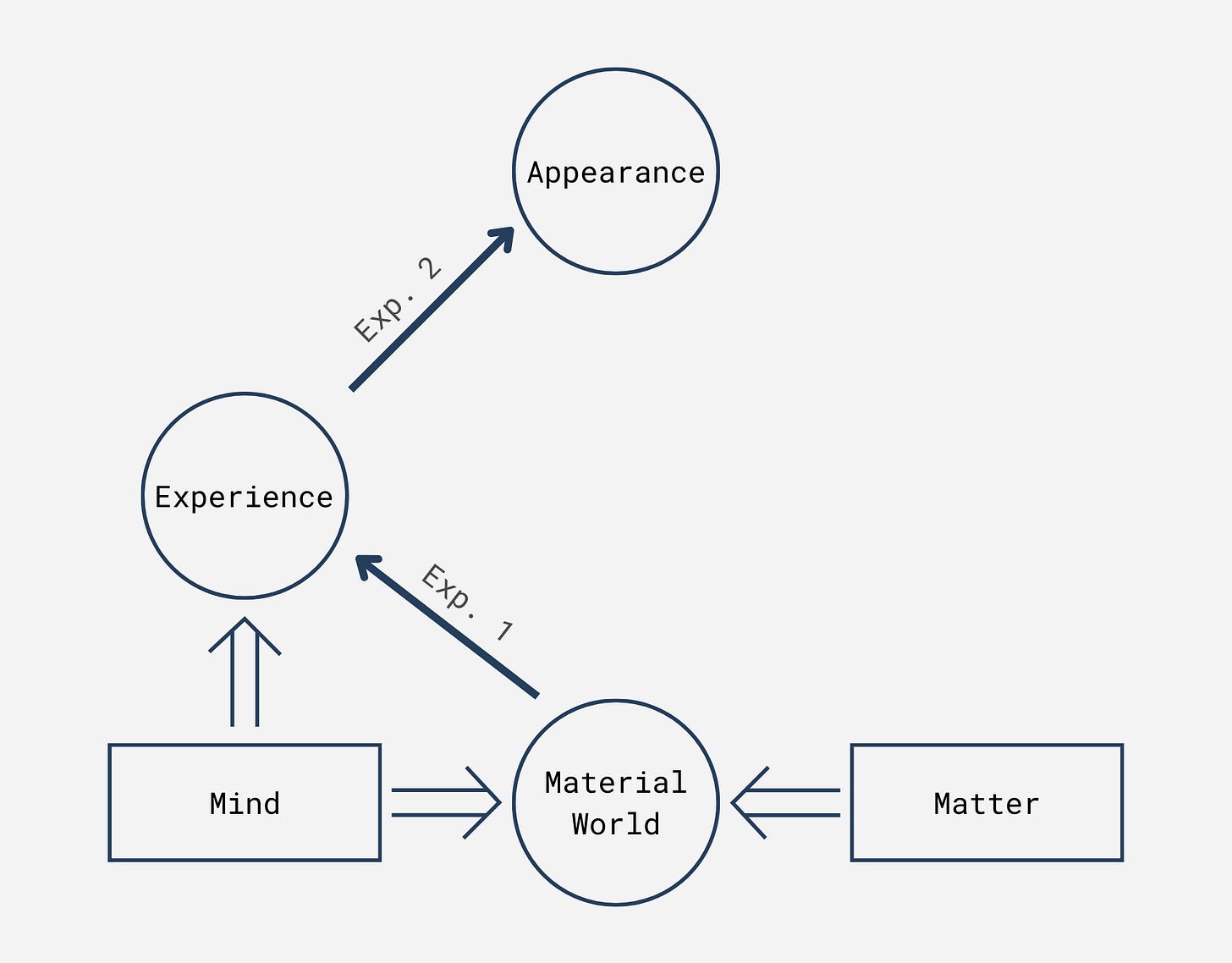

Immediately following, yet another experiment was introduced, as a two-step combination of Experiments 1 and 2, labeled as "Experiment 1+2: matter as experience as appearance." In both cases the endpoint was pure appearance, corresponding to what would much later be introduced as A in the blackboard diagram, Fig. 51, where it was labeled as "Non-dualistic pure appearance."

Where should we put "Appearance" with respect to what we already built up in Fig. 61? Vertically, it probably should move upwards, given that we have made one more step outwards in the blackboard diagram. This suggests that we would expect to move up two steps from the baseline of the natural attitude. But what about the horizontal dimension? Should it move one more step to the left from "Experience" in Fig. 61 or "E=S" in Fig. 62, since it leaves both experience and subjective mind behind? Or would it be simpler to draw the line to A just straight upwards?

At this stage it is not yet fully clear what would provide the best fit, but in the next couple entries, after we add a few more nodes to the figure, it will become clear that the most natural position is the one indicated in Figs. 63 and 64, below. For now, the following motivation already gives us a strong hint. Since A is non-dual, beyond subject-object duality, it should neither be placed above "Mind," nor above "Matter". The most logical place is in the middle, above "World."

The next step in theory

So far we have followed philosophy, one step up and above Husserl's natural attitude, leading to what he described as the result of his epoché. We have also followed Nishida's hybrid approach in which he was trying to forge new philosophical approaches, with inspiration from Zen Buddhism, an example of a non-dualistic type of contemplative tradition in our terminology.

In our next entry, we will pose the question: now that we have embellished the mind side of things with two arrows associated with two philosophers, what can we do on the matter side of things? Should the science of matter stay on the same level as the original baseline of Fig. 57, as Husserl strongly argued for, with complete conviction? Or should it be pushed even further down than the natural attitude, given the tendency of sometimes extreme reductionism expressed by many scientists, past and present? William Blake and Wolfgang von Goethe would agree with that move downward, in reaction to the clockwork picture of mainstream science in their days. Goethe went as far as trying to construct a whole new parallel science of matter. Or . . . is there a third option? Stay tuned! The next entry will have more to say about all this.

Meanwhile, as promised, we will continue with an experimental corner in this entry, as well as future entries in the FEST log.

The next step in experimentation

In entry #019 the notion of subject-object reversal, s/o reversal for short, was introduced by letting a tree look at you. That was experiment 3a. In the previous entry, #020, we introduced two new novel ways of experimenting with the idea of s/o reversal, experiments 3b and 3c. If you haven't had the opportunity to try those out yet, now would be a great time to do so before reading the text below. This will help you approach the new additions with a fresh perspective. Here is the first extension:

Experiment 3b: s/o reversal with our whole field of vision

The instruction in the previous entry was: "Instead of letting one object look at you, let everything in your field of vision look at you, simultaneously." As before, the reports from different people differed significantly, but one common element jumped out for many people, though certainly not for all: an increased awareness of the front side of one's body, the side that "everything" in front of oneself was looking at. As for the second extension:

Experiment 3c: s/o reversal with everything behind you

The instruction here was: "Now let everything behind you, well outside your field of vision, look at you." In this case, as you might have guessed, a typical response was to become more aware of your back. We tend not to think much about our backs compared to, say, our feet or our hands or our necks, which are all more movable, and in the first two cases fully visible.

The shift in awareness from the front to the back of our body may not have been surprising. However, alongside that shift, many people reported experiencing an uncanny feeling and an urge to turn around, despite being instructed not to do so. Logically, it makes sense to want to glance back when we are told that a whole bunch of "lookers" are watching us from behind.

However, logic is not the point of the experiment. More important is to actually experience this physical reaction in our own embodiment, independent of whether or not it is easy to explain. Isn't it interesting that we can so easily induce vivid physical feelings, just by imagining that whatever is behind us is now looking at us? Now that is an example of studying the mind by using the mind.

Switching from sight to sound

How about doing a s/o reversal with sounds, instead of vision? Almost everywhere we find ourselves, there are sounds. And if you are in a very quiet environment, chances are you can feel or even hear your heartbeat. First, listen to the sounds you hear for a little while. Then reverse the relationship: let the sounds listen to you.

What do you experience, and how is the experience different from letting a visible object look at you?

After a while, you may notice that you have a choice. Let's say you are in a kitchen and you hear a kettle whistle. One option is to let the kettle listen to you instead. Another option is to let the sound of the kettle listen to you. Let's give those two different options different numbers:

Experiment 3d: let a sound-emitting object hear you

Experiment 3e: let a sound hear you

Note that, returning to the very first s/o reversal where you let a tree look at you, we had the same choice! We could let ourselves be seen by the tree. But we could also let ourselves be seen by the light that was painting the tree in our field of vision.

Almost certainly you chose the first option, as the more natural one. Isn't it interesting that with a sound it is less clear which option is more natural, to let a sound listen to you or to let the sound producing object listen to you?

In fact, when you are walking around in a city, you will hear many sounds for which it is not even clear what kind of object is emitting that sound. In that case your only option is to do s/o reversal with the sound.

Note also that it is hard to imagine that you can do s/o reversal with an image of an object without being able to do so with the object itself. There may be exceptions, like the occurrence of a rainbow, but in most cases the image belongs to a particular object. Or . . . to more than one object! Seeing the Moon reflected in a pond, you can choose to focus on the Moon or on the pond; or on the water in the pond if you want to be even more precise.

Let us end here, with a quote from Dogen, a famous 13th century Japanese Zen teacher, who started the Japanese Soto Zen School. When viewing the reflection of the Moon in a dewdrop, his response was:

The depth of the dewdrop is the height of the Moon.